API Design Principles

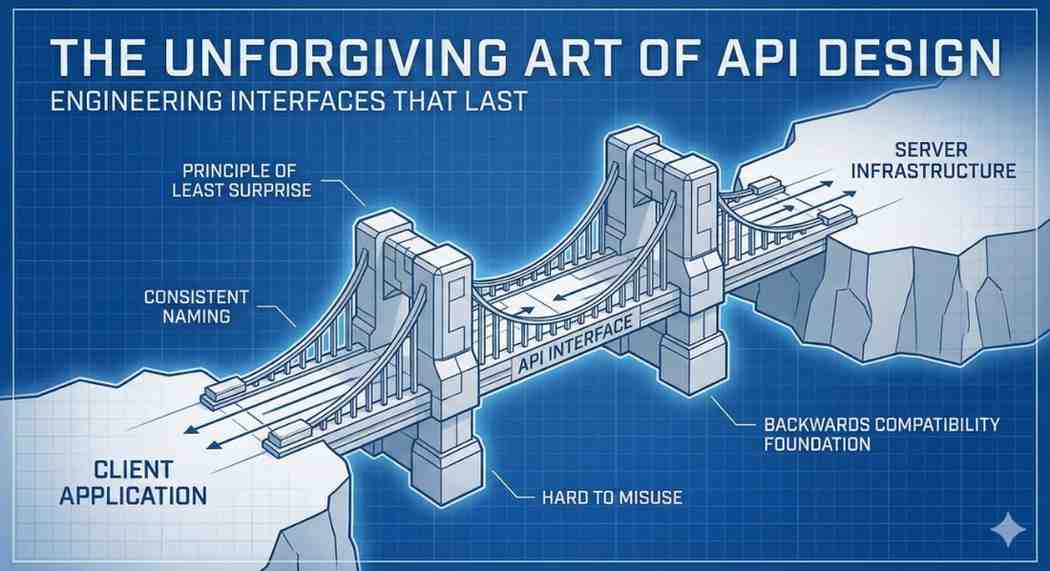

If you write code, you are an API designer. Whether you are exposing a RESTful service to the world or simply writing a helper class for a colleague three desks away, you are creating an interface that defines how others interact with your logic.

The catch? Code is ephemeral, but APIs are forever. Once your interface has users, changing it becomes a massive liability. A bad internal implementation can be refactored silently; a bad API design requires breaking changes, migration guides, and frustrated users.

Drawing from recent educational materials on object-oriented design, I want to explore the philosophy and tactical guidelines for building APIs that are robust, intuitive, and remarkably boring (in the best way possible).

The Philosophy: Characteristics of a “Good” API

What separates a library you love from one you tolerate? It usually boils down to the “Principle of Least Surprise”. A great API minimizes the cognitive load required to map a user’s intent to code execution.

1. Hard to Misuse

This is the hallmark of secure and robust design. A well-designed API should make the correct path the easiest path. It shouldn’t force the user to memorize implicit ordering of method calls.

The Scenario: Imagine a cryptographic library.

- Bad Design: You must call

initialize(), then set the key, then set the mode, and only then callencrypt(). If you mix the order, it crashes or, worse, encrypts insecurely. - Good Design: The constructor requires the key and mode immediately, or a builder pattern enforces the order at compile time. The state space is small and well-defined.

2. Easy to Memorize via Consistency

Consistency reduces the need for documentation. If you use the verb fetch for network requests in one module, do not switch to retrieve or get in another . If your naming conventions are predictable, users can guess method names without hitting Ctrl+Space.

3. Minimal Boilerplate

If a user needs to write 20 lines of configuration just to say “Hello World,” your API has failed. The interface should be “complete” enough to handle complex tasks, but accessible enough to get up and running in three lines of code for the basic scenario: instantiation, basic configuration, and execution.

The 3-line limit is a metric for the minimum code required to use the API (the “Hello World” case), not a maximum limit for complex, customized configurations.

The Design Process: Code Last, Specs First

The biggest mistake is implementing the logic first and then slapping an interface on top of it. This usually results in an API that leaks implementation details.

The “Wishful Thinking” Approach

Before you write a single line of implementation, write the client code that consumes it.

Suppose I am building a log ingestion client. I should start by writing the ideal usage scenario in my editor:

1

2

3

// I wish I could use the library like this:

LogIngester client = LogIngester.connect("api.server.com");

client.send(LogLevel.ERROR, "System failure imminent");

If this code looks clean and readable, then I start implementing the LogIngester class. This approach forces the implementation to adapt to the user, rather than forcing the user to adapt to the database schema or network protocol underlying the code.

Review and Feedback

Since APIs are hard to change, peer review is critical before publication. Write a one-page spec or a few example use cases and pass them to a colleague. If they misinterpret a method name or struggle to understand a parameter, fix the design, not the documentation.

Tactical Guidelines for the Trenches

Here are specific, battle-tested rules for the implementation phase, synthesized from industry best practices.

1. Naming is Semantics

Names should read like prose. Avoid abbreviations unless they are universally standardized (like min or max).

- Avoid:

usr.calc_exp()(Ambiguous: calculate expiration? experience? expense?) - Prefer:

user.calculateExperiencePoints()

Furthermore, avoid “false consistency.” Do not use the prefix set if the method performs a complex calculation rather than a simple property assignment.

2. The “Three-Line” Rule & Defaults

Users should be able to instantiate your object, set a basic configuration, and execute the primary function in three lines or fewer . This requires sensible defaults.

If your ImageCompressor has 50 tuning parameters, 49 of them should have default values that work for 80% of users. Do not force the user to decide on a “Huffman Table Optimization Strategy” just to resize a JPEG.

3. Fail Fast and Loud

When things go wrong, the API should report it immediately. The worst APIs are those that fail silently or return null when an error occurs.

- Validation: Check arguments at the very start of the method.

- Exceptions: Prefer unchecked exceptions for programming errors (like passing

nullwhere it’s not allowed). - Clarity: The exception message should not just say “Error.” It should explain what happened and how to fix it.

4. Minimize Mutability

Unless there is a compelling performance reason, prefer immutable objects. Mutable objects require defensive copying and are nightmares in multi-threaded environments. If you return a collection, return an unmodifiable view so the user can’t accidentally break your internal state.

5. Performance vs. Purity

There is often a temptation to warp an API to make it faster. Resist this. Design the API for clarity and correctness first. Good design usually coincides with good performance, but a convoluted API optimized for a specific micro-benchmark will cause maintenance headaches forever .

6. Speak the Local Dialect

APIs do not exist in a vacuum; they belong to a specific ecosystem. Do not force Java conventions onto a Python developer, or C# idioms onto a JavaScript user. If you are porting a library from one language to another, you must translate the style as well as the logic. Conventions: Respect the local rules for capitalization, getters/setters, and exception handling .

- A Python user should feel like they are using a native Python library, not a wrapper around a Java class. If your API feels “foreign,” developers will struggle to adopt it

The Golden Rule: Backwards Compatibility

If you take nothing else away from this post, remember this: You can add, but you can never remove.

Once an API is public, you cannot simply rename a method because you found a better word. You must support the old method, mark it as deprecated, and maintain it for a reasonable lifecycle. This is why “When in doubt, leave it out” is the safest strategy. It is much easier to add a feature later than to remove a mistake that users are relying on.

Design is about empathy. It is about understanding the frustration of the developer who will use your tool six months from now—and that developer might just be you.

Source Acknowledgment: This post is based on my interpretation of “API Design Guidelines” and lectures by Dr. Balázs Simon, BME.