Code Intelligence: Bridging Static Analysis and Generative AI

The landscape of software development tools is undergoing a fundamental shift. For decades, our “intelligent” tools—IDEs, linters, and refactoring engines—were built on deterministic logic. Today, we are layering probabilistic models on top of those foundations. As software engineers, it is critical to understand not just how to use these AI assistants, but how they function under the hood, where they fail, and how they complement traditional engineering methods.

Deterministic logic refers to a system, process, or algorithm where a specific input always produces the exact same output, with no randomness or uncertainty involved.

In this post, I will dissect the two dominant paradigms of code intelligence: the structural rigidity of syntax trees and the statistical fluidity of Large Language Models (LLMs).

1. The Deterministic Foundation: ASTs and DOMs

Before the advent of generative AI, “code intelligence” referred to a tool’s ability to understand the formal structure of a program. This approach relies on parsing source code into strict hierarchical models.

- Concrete vs. Abstract Syntax: Tools distinguish between the raw text (concrete syntax) and the logical structure (Abstract Syntax Tree or AST). For example, an AST represents a

whileloop not as the string"while", but as a node containing a condition branch and a body branch . - The Graph Approach: Advanced modeling often visualizes code as graph-based structures. This allows algorithms to traverse relationships, enabling features like “Find All References” or “Call Hierarchy” with 100% precision .

The Engineering Trade-off: This method is mathematically sound. If a rename-refactoring tool is bug-free, it is guaranteed to change every correct instance of a variable. However, it is brittle; it cannot understand natural language comments, nor can it offer suggestions for incomplete code that doesn’t yet parse correctly.

2. The Probabilistic Shift: Machine Learning and LLMs

The modern wave of intelligence treats code not as a tree, but as a sequence of data, leveraging statistical probability rather than formal grammar.

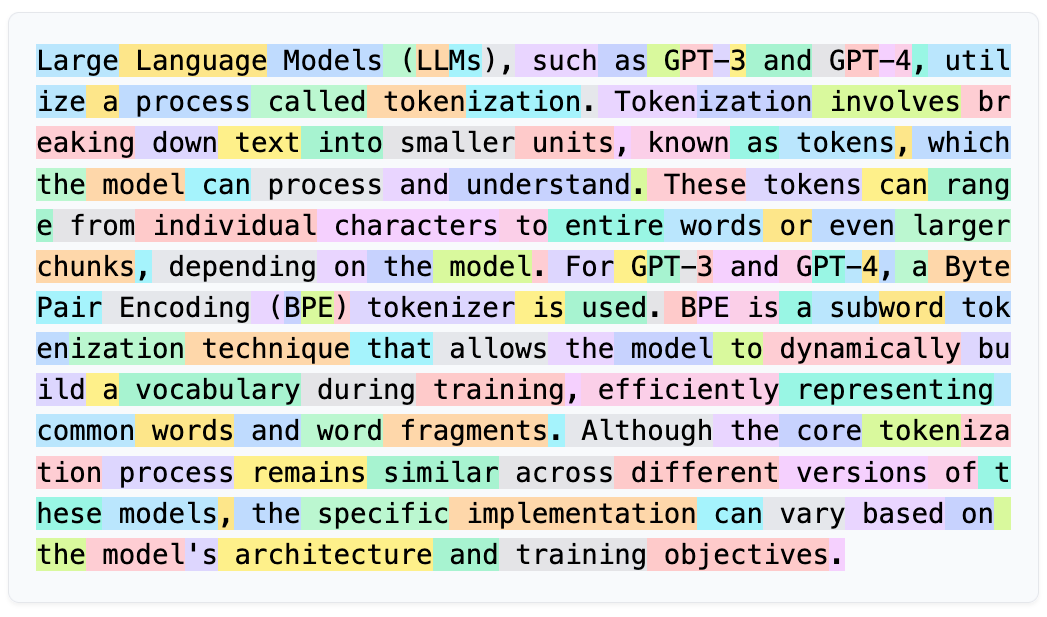

Tokenization and Sequence Modeling

At the core of technologies like GPT-4 or Copilot is tokenization. Code is broken down into numerical chunks (tokens)—variables, keywords, and even whitespace are converted into high-dimensional vectors. The model does not “know” Python grammar in the traditional sense; it predicts the most likely next token based on patterns learned from terabytes of training data .

Example: If the input sequence is public void calculate, the model calculates a probability distribution for the next token. It might assign a high probability to Total or Price, and a near-zero probability to class .

The Agent Architecture

We are moving beyond simple autocomplete toward Agentic Systems. These systems wrap the LLM with engineering scaffolding to overcome the model’s limitations:

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG): Since an LLM cannot fit an entire legacy codebase into its context window, agents use retrieval mechanisms (like

vector similarity search) to fetch only the relevant snippets before generating an answer .Vector similarity search is like searching bymeaning: you type an idea, and the system finds results that are conceptually similar, even if the exact words are different. Scope-based search is like searching within boundaries : you only look in specific categories, dates, users, or permissions, and results outside those limits are ignored. Simply put, vector search finds related content, while scope-based search controls where the search is allowed to look.

Tool Execution: Advanced agents can be prompted to output machine-readable commands (e.g., JSON). They can “decide” to run a unit test or query a database, parse the result, and then continue their reasoning. This loop allows the agent to verify its own hallucinations .

Tool Execution

1. Bridging the Gap Between Text and Action

By default, Large Language Models (LLMs) output natural language, which is difficult for other software programs to use. To solve this, agents are instructed to generate machine-readable commands, usually in JSON format. For example, instead of saying “I will look for the file,” the model outputs:

{"action": "search_files", "pattern": "*.py"}.

2. The Feedback Loop

Tool execution involves a specific loop that helps the agent “think” more clearly:

- Request: The agent realizes it needs more information or needs to perform a task (like running a unit test).

- Execution: The system parses the JSON, runs the actual tool in a sandboxed environment (to prevent accidental damage), and captures the output.

- Integration: The result of the tool (e.g., “Test Failed: Syntax Error at line 10”) is fed back into the agent’s prompt history.

3. Remediating Hallucinations

LLMs are notoriously bad at precise logic or math—they might confidently state that a complex calculation is correct when it isn’t (a “hallucination”).

Manual vs. Tool: Instead of guessing the result of a calculation or the behavior of a function, the agent generates Python code to perform the calculation or runs the function itself.

Verification: By seeing the actual output of the code it just wrote, the agent can catch its own mistakes and correct its reasoning before giving you the final answer.

Common Tools Used by Agents

- File Operations: Creating, renaming, or deleting files.

- Code Execution: Running Python scripts or unit tests to verify logic.

- Search: Finding files or specific symbols (variables/functions) across a repository.

- Logic Reasoning: Passing a design to a formal tool to ensure it is valid and consistent.

3. Neuro-Symbolic Reasoning: The Best of Both Worlds

A purely statistical model is prone to “hallucination”—confidently generating code that calls non-existent libraries or violates type safety . The frontier of research lies in Neuro-Symbolic AI, which combines the creativity of ML with the rigors of logical reasoning.

In this architecture:

- The Neural Network acts as the creative engine, translating vague natural language requirements into a draft solution (e.g., a draft software model or code snippet).

- The Symbolic Engine acts as the guardrail, applying logic reasoning, syntax checking, and graph transformation rules to ensure the output is valid and consistent .

This is particularly useful in modeling. An LLM might struggle to draw a complex graph directly, but it can easily generate a textual representation (like PlantUML) which a symbolic tool can then render and validate .

4. Ethical and Practical Obligations

As we integrate these stochastic tools into our workflows, we assume new responsibilities.

- Verification is Mandatory: LLMs provide probabilistic guarantees, not correctness guarantees. There have been legal cases where professionals cited non-existent precedents generated by AI. In code, this manifests as subtle logic bugs or security vulnerabilities. The engineer must verify every line .

- Copyright awareness: These models are trained on open-source code but do not inherently respect license boundaries. If an LLM reproduces a large chunk of GPL-licensed code verbatim, the user is liable for the attribution and licensing compliance .

- Sustainability: We must be mindful of the “cost” of intelligence. Using a trillion-parameter model to rename a variable is inefficient compared to a lightweight AST operation. We should reserve heavy-compute AI for tasks that actually require natural language understanding or complex synthesis .

Conclusion

The future of code intelligence is hybrid. We will not abandon the precision of AST-based tools for the unpredictability of AI. Instead, we will see a convergence where AI handles the “fuzzy” edge of intent and composition, while static analysis ensures the structural integrity of the result.

Attribution: This post is a synthesis of concepts derived from the “Code and Model Intelligence” lecture materials by the Critical Systems Research Group (BME Faculty of Electrical Engineering and Informatics).