Data Access Layer: From ORM to Architectural Patterns

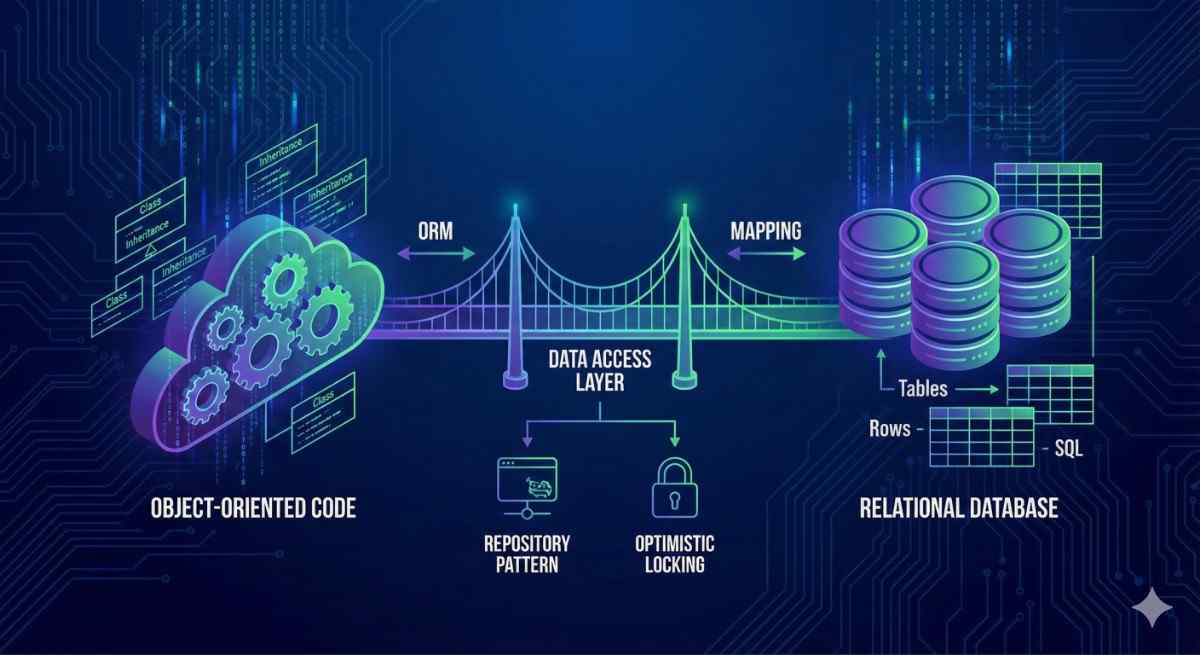

In modern software architecture, few boundaries are as critical—and as often mishandled—as the line between your application’s business logic and its data storage. We often treat the database as a black box, but the “Data Access Layer” (DAL) requires careful engineering to bridge the gap between the object-oriented world of our code and the relational world of our data.

In this post, I want to break down the core mechanics of Object-Relational Mapping (ORM), handling concurrency in stateless environments, and the evolution of the Repository pattern.

The Impedance Mismatch: Objects vs. Relations

The fundamental challenge of any DAL is the “impedance mismatch.” We think in graphs of objects (inheritance, polymorphism, references), but databases store flat sets of rows (foreign keys, normalization). Bridging this gap is the primary job of an ORM.

The Problem of Inheritance

Consider a payment system. In your code, you likely have an abstract PaymentMethod class with subclasses like CreditCard and BankTransfer. Relational databases, however, do not support inheritance natively.

We generally have three strategies to map this hierarchy to tables, each with specific trade-offs regarding performance and data integrity.

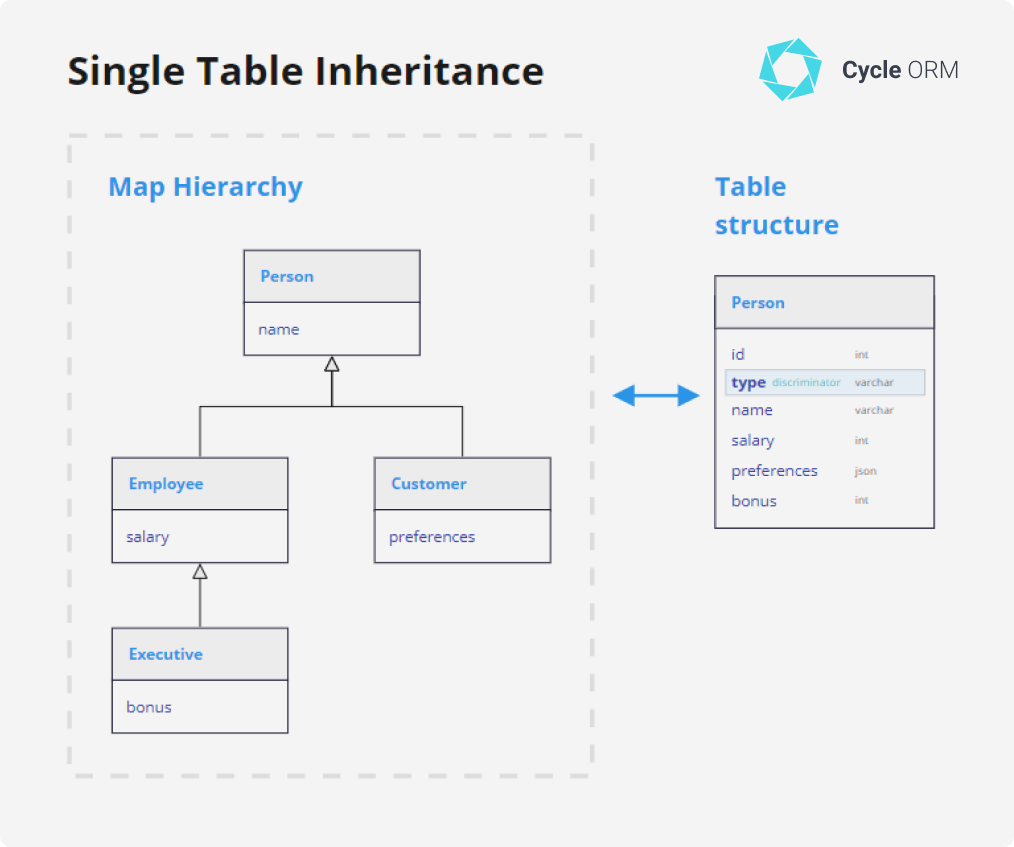

1. Single Table Inheritance (Table-per-Hierarchy)

We map the entire class hierarchy to one table.

- Structure: One

PaymentMethodstable containing columns for all subclasses (CardNumber,IBAN,SwiftCode). - Discriminator: A column (e.g.,

Type) distinguishes rows. - Pros: Very fast (no joins).

- Cons: Columns must be nullable, wasting space and weakening SQL constraints (e.g., you can’t enforce

IBANis not null at the DB level for bank transfers only).

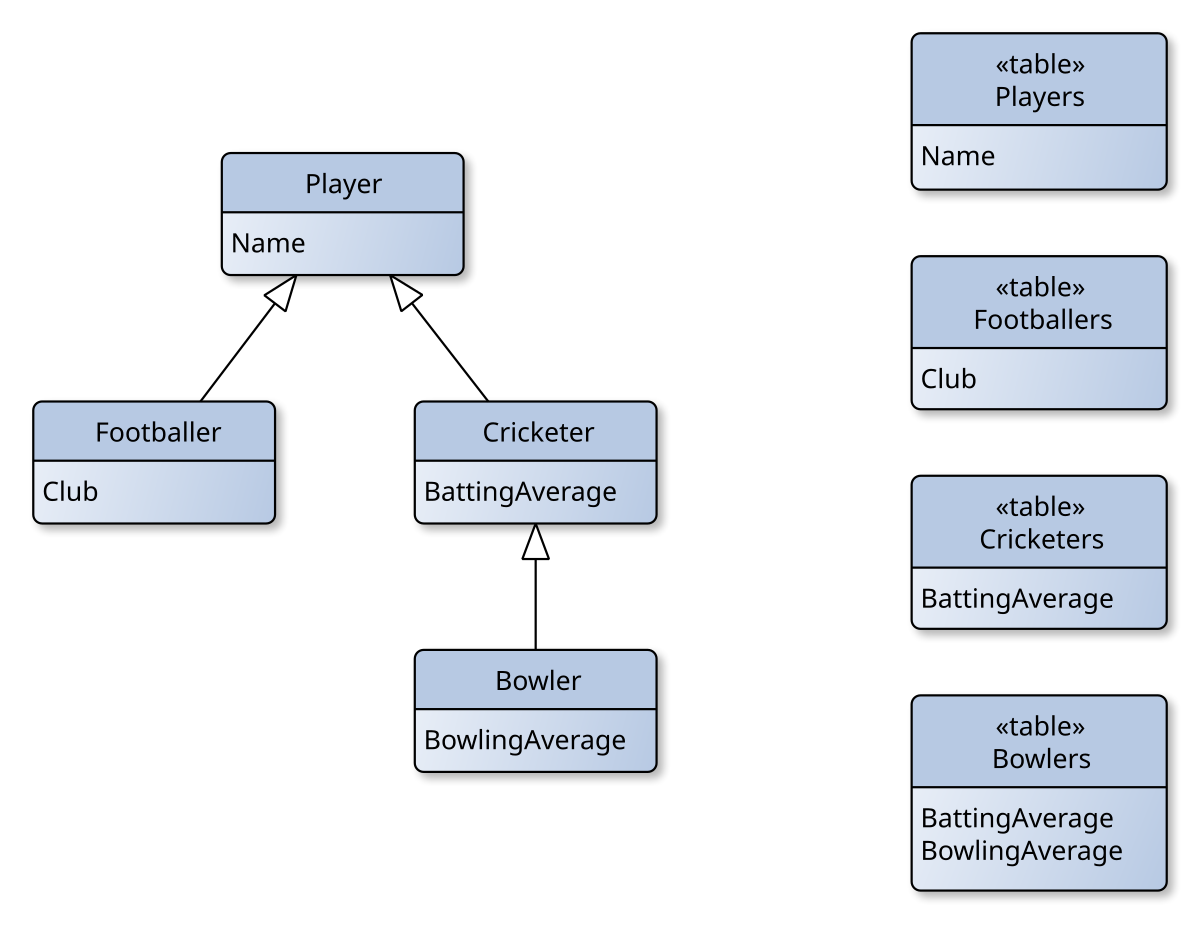

2. Class Table Inheritance (Table-per-Type)

We create a table for the base class and separate tables for each subclass.

- Structure:

PaymentMethods(ID, Owner),CreditCards(ID, CardNumber),BankTransfers(ID, IBAN). - Pros: Normalized; clean constraints.

- Cons: Retrieving a polymorphic list requires complex

JOINs, which can kill performance on large datasets.

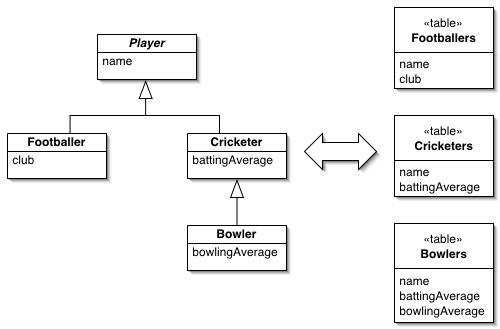

3. Concrete Table Inheritance (Table-per-Concrete-Class)

We create tables only for the non-abstract classes.

- Structure: A

CreditCardstable and aBankTransferstable. Both contain the base columns (Owner). - Pros: Fast access for specific types.

- Cons: Polymorphic queries (e.g., “Get all payment methods for User X”) are difficult, often requiring

UNIONoperations. ID management becomes tricky (ensuring IDs are unique across tables).

Code & Schema Illustration:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

// Domain Model

public abstract class PaymentMethod {

public int Id { get; set; }

public string OwnerName { get; set; }

}

public class CreditCard : PaymentMethod {

public string CardNumber { get; set; }

}

public class BankTransfer : PaymentMethod {

public string IBAN { get; set; }

}

If we choose Single Table Inheritance, our SQL looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

CREATE TABLE PaymentMethods (

Id INT PRIMARY KEY,

Discriminator VARCHAR(50) NOT NULL, -- 'CC' or 'BT'

OwnerName VARCHAR(100),

CardNumber VARCHAR(20) NULL, -- Nullable for BankTransfer

IBAN VARCHAR(30) NULL -- Nullable for CreditCard

);

The “Shadow Information” Problem

To make persistence work, our domain objects often get polluted with “shadow information”—data that has no business meaning but is required for the database.

- Foreign Keys: In a pure OO model, a

Orderhas a reference to aCustomerobject. In the DB,Orderhas aCustomerIdinteger. - Concurrency Tokens: Timestamps or version numbers added solely to detect conflicting updates.

A good architectural goal is to keep this shadow info out of the pure domain logic, though in practice, pragmatism often wins, and we expose IDs on our entities.

Concurrency Control in Stateless Apps

In web applications, we face a specific concurrency challenge: The Lost Update.

Imagine two admins, Alice and Bob, open the same product page to edit the price.

- Alice reads Product A (Price: $100).

- Bob reads Product A (Price: $100).

- Alice saves Price as $120.

- Bob saves Price as $110.

If we don’t handle this, Bob’s save overwrites Alice’s, and her change is lost without a trace. Since HTTP is stateless, the database doesn’t know Bob was looking at an outdated version of the data when he clicked save.

Solution: Optimistic Locking

Pessimistic locking (locking the row when Alice reads it) is rarely viable in web apps because it kills scalability. The standard solution is Optimistic Locking.

We add a Version (or Timestamp) column to the entity.

The Workflow:

- Alice reads Product A (Version: 1).

- Bob reads Product A (Version: 1).

- Alice saves. The system updates

WHERE Id=A AND Version=1, increments Version to 2. Success. - Bob saves. The system attempts update

WHERE Id=A AND Version=1. - Fail: The database finds no rows because the current version is 2. The system throws a

ConcurrencyException.

Implementation Logic:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

public void UpdateProductPrice(int productId, decimal newPrice, int originalVersion)

{

// The SQL generated effectively looks like:

// UPDATE Products

// SET Price = @Price, Version = Version + 1

// WHERE Id = @Id AND Version = @OriginalVersion;

var rowsAffected = _db.ExecuteUpdate(productId, newPrice, originalVersion);

if (rowsAffected == 0)

{

// This means someone else changed the record between our read and write

throw new DataConcurrencyException("The record was modified by another user.");

}

}

This forces the UI to handle the conflict—usually by asking the user to reload the data and re-apply their changes.

The Repository Pattern

The Repository pattern is perhaps the most discussed pattern in DAL design. Its core purpose is abstraction: it presents the data storage as an in-memory collection of objects, hiding the ugly details of SQL, connections, and cursors.

The Ideal Generic Repository

A common approach is to define a generic interface to standardize data access across the application.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

public interface IRepository<T> where T : class

{

T GetById(int id);

void Add(T entity);

void Remove(T entity);

// The controversial part: querying

IEnumerable<T> Find(ISpecification<T> spec);

}

This allows us to write business logic that is unit-testable. We can mock IRepository<T> easily, whereas mocking a database connection is painful.

The “Leaky Abstraction” Trap

A major risk with Repositories is returning IQueryable (in .NET) or similar query builders directly to the Business Logic Layer (BLL).

1

2

3

4

// BAD PRACTICE

public IQueryable<User> GetAll() {

return _dbContext.Users;

}

If your BLL looks like this: repo.GetAll().Where(u => u.Name == "John").ToList(), you have leaked data access concerns into your business logic. The SQL is not executed inside the repository but triggered by the BLL. This couples your business logic to the capabilities of your ORM provider and makes performance tuning difficult.

Best Practice: Keep the query logic inside the repository or encapsulated in “Specification” objects.

Is the Repository Pattern Dead?

With modern ORMs like Entity Framework (EF) Core or Hibernate, there is a valid argument that the ORM itself is the Repository.

- EF’s

DbContextacts as the Unit of Work. - EF’s

DbSetacts as the Repository.

Adding a custom Repository layer on top of a modern ORM is often redundant (an “abstraction over an abstraction”).

When to use a Repository:

- Strict Layering: You need to swap the data source later (e.g., moving from SQL Server to a microservice or NoSQL).

- Testing: You rely heavily on mocking data access for pure unit tests.

When to skip it:

- Simple Apps: You are building a CRUD app tightly coupled to a relational DB.

- YAGNI (You Ain’t Gonna Need It): Don’t over-engineer for a database switch that will likely never happen.

Conclusion

Designing a Data Access Layer is about balancing purity with pragmatism.

- Mapping: Choose inheritance strategies based on how you query the data, not just how your classes look.

- Concurrency: Always implement optimistic locking for web-facing entities; the “last writer wins” default is dangerous.

- Architecture: Use the Repository pattern if you need testability or abstraction, but don’t be afraid to use your ORM directly if your application structure allows it. Complexity is a cost; only pay it if it buys you value.

Acknowledgment: This blog post is based on an interpretation of educational materials on Data Access Layers and OR Mapping concepts of Data-Driven Systems course BME AUT.