Object-Oriented Design Heuristics

Software design is rarely a binary choice between correct and incorrect. Rather, it involves navigating trade-offs to achieve maintainability and flexibility. While strict rules can be rigid, design heuristics serve as pragmatic guidelines—principles derived from experience that steer developers toward robust architecture.

This article explores the core heuristics of object-oriented design, categorized into class design, responsibility distribution, object relationships, and inheritance hierarchies.

1. Class Design and Encapsulation

The fundamental building block of an object-oriented system is the class. Properly designing classes requires strict adherence to encapsulation and cohesion.

The Privacy of Attributes

A primary rule of encapsulation is that attributes should always be private. Exposing state via public or protected attributes violates information hiding and creates maintenance issues if the internal representation changes. Access to state should be provided strictly through public methods that enforce invariants.

Cohesion: Binding Data and Behavior

A common anti-pattern is the separation of an object’s data from its logic, leading to “data holder” classes (structs) and “manager” classes. Heuristics dictate that related data and behavior must be kept together. A class should capture exactly one abstraction or responsibility; if a class captures multiple responsibilities, it likely violates the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) and should be split.

Example: Encapsulating Logic

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

// Poor Design: Data and behavior are separated

public class Point {

public double X;

public double Y;

}

// Improved Design: Data is private; behavior is exposed

public class Point {

private double _x;

private double _y;

public void SetPolar(double r, double phi) {

_x = r * Math.Cos(phi);

_y = r * Math.Sin(phi);

}

}

Interface Design

The public interface of a class should be minimal. Exposing internal helper methods or offering multiple ways to perform the same action clutters the interface and confuses the user. Furthermore, classes should not depend on their users; dependencies should flow from the user to the used class, or be inverted via interfaces.

2. Managing Responsibilities and Coupling

Once classes are defined, the next challenge is distributing responsibilities among them without creating tight coupling.

The “God Class” and Distribution

Responsibilities should be distributed horizontally and evenly across the system. A “God Class” (a class that knows or does too much) indicates a failure to decompose the problem effectively. Conversely, developers should avoid creating classes that serve purely as methods (e.g., a class named Mover with a single Move method), as this misplaces behavior.

The Limits of Collaboration

High coupling reduces system flexibility. A heuristic for managing complexity is to minimize the number of collaborating classes. A single class should collaborate with no more than approximately seven other classes. This limit aligns with human cognitive limits regarding short-term memory.

Modeling the Real World

To make responsibilities intuitive, design should model the real world where possible. However, this is bounded by the system’s domain; developers should not model actors outside the system (such as the user) or physical devices, but rather the interfaces that represent them. Additionally, the “View” (UI) should always depend on the “Model” (logic), never the reverse.

3. Object Relationships: Association and Containment

How objects reference one another is critical for decoupling.

Containment over Association

When a class requires another object to function, containment (composition) is preferred over association. Containment implies a strong “has-a” relationship where the container manages the lifecycle of the contained object.

Interaction Guidelines

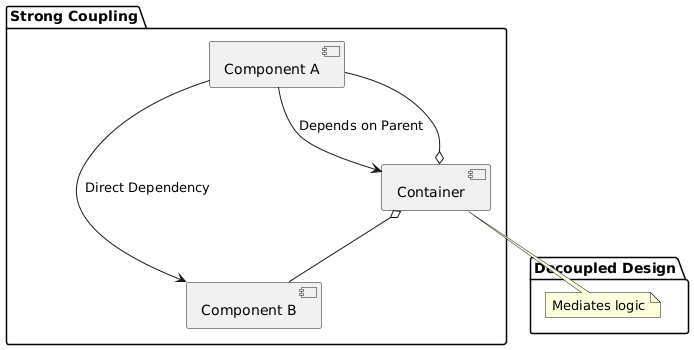

To maintain modularity, specific interaction rules apply to containment hierarchies:

- Utilization: A container should use its contained objects to perform tasks rather than returning them to the client. Returning contained objects violates the

Law of Demeterand exposes internal structure. - Independence: A contained object should not know about or depend on its container. If communication is necessary, it should occur via events or callback interfaces.

- Sibling Decoupling: Objects contained within the same parent should not communicate directly with one another. The container should mediate their interactions to prevent invisible coupling between components.

Visualizing Decoupled Relationships:

4. Inheritance and Polymorphism

Inheritance is a powerful mechanism often misused for code reuse rather than behavior specialization.

Behavior Specialization vs. Data Reuse

Inheritance should be reserved for behavior specialization (the “IS-A” relationship). It should never be used solely to reuse code or data from a base class. If data reuse is the primary goal, containment is the correct approach.

The Open-Closed Principle (OCP)

A base class should never depend on its derived classes. Explicitly checking the type of an object (e.g., if (x is SubType)) violates the Open-Closed Principle, as adding a new subclass requires modifying the base logic.

Polymorphism Over Type Checking

Heuristics strongly advise against type checking (e.g., instanceof) or using “type codes” (enums) to determine behavior. Instead, behavior should be polymorphic: define a method in the base class or interface and override it in the derived classes.

Code Example: Polymorphism vs. Type Checking

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// Violation: Explicit type checking reduces maintainability

public void Handle(Monster m) {

[cite_start]if (m is BlueMonster) { /* Logic A */ } // [cite: 1308]

else if (m is RedMonster) { /* Logic B */ }

}

// Correction: Polymorphic dispatch

public void Handle(Monster m) {

m.PerformAction(); // The object decides behavior [cite: 1323]

}

Hierarchy Structure

- Abstract Roots: The root of an inheritance hierarchy should ideally be an abstract class or an interface.

- Depth: Inheritance hierarchies should be deep enough to provide useful taxonomy but should generally not exceed seven levels to remain understandable.

- No Empty Overrides: If a subclass overrides a method with an empty implementation, it suggests the inheritance hierarchy is flawed and the subclass does not truly fit the abstraction.

5. Constraints and Semantics

Robust design must enforce system constraints effectively.

- Static Constraints: Constraints that never change should be encoded in the model’s structure. For example, if a specific object type must never possess a certain component, that field should not exist in the class.

- Example: Think of a Bicycle vs. a Car. You don’t write a rule for a Bicycle saying “Fuel capacity must be 0.” Instead, the

Bicycleclass simply does not have afuelTankfield. It is structurally impossible to put gas in it.

- Example: Think of a Bicycle vs. a Car. You don’t write a rule for a Bicycle saying “Fuel capacity must be 0.” Instead, the

- Dynamic Constraints: Constraints that depend on input or configuration should be enforced in the constructor to prevent the instantiation of invalid objects.

- Example: Think of a** Triangle**. A triangle with sides

1,2, and50is geometrically impossible (the lines wouldn’t touch). The constructornew Triangle(1, 2, 50)should throw an exception immediately. It is better to crash now than to create a “broken” shape that causes weird calculation errors hours later.

- Example: Think of a** Triangle**. A triangle with sides

- State-Based Constraints: Dynamic constraints relying on the object’s current state (e.g., “cannot action if empty”) should be checked at the beginning of the relevant behavioral methods.

- Example: Think of an ATM. Your bank account is valid, and the ATM is working, but you cannot withdraw money if your balance is zero. The

withdraw(amount)method must first checkif (balance >= amount). If you try to withdraw from an empty account, the action is blocked, but the account object itself remains valid.

- Example: Think of an ATM. Your bank account is valid, and the ATM is working, but you cannot withdraw money if your balance is zero. The

Conclusion

These heuristics provide a framework for navigating the complexities of software architecture. While they are not absolute laws, adhering to principles such as Single Responsibility, Containment over Inheritance, and Polymorphism typically yields systems that are more modular, testable, and maintainable. The goal is to make informed trade-offs that best suit the specific requirements of the application.

Source Acknowledgment:This post is based on my personal notes and interpretation of the “Object-Oriented Design Heuristics” lecture materials by Dr. Balázs Simon (BME, IIT).