MongoDB Architecture and .NET Implementation

As software engineers, we often hit a specific friction point with traditional Relational Database Management Systems (RDBMS): the rigidity of the schema. When an application evolves for over a decade, tables accumulate, column counts explode, and simple migrations become high-risk operations.

This post synthesizes the core concepts of MongoDB as a solution to these scalability and flexibility hurdles, focusing on architectural decisions, schema design in a document-oriented world, and practical implementation in the .NET ecosystem.

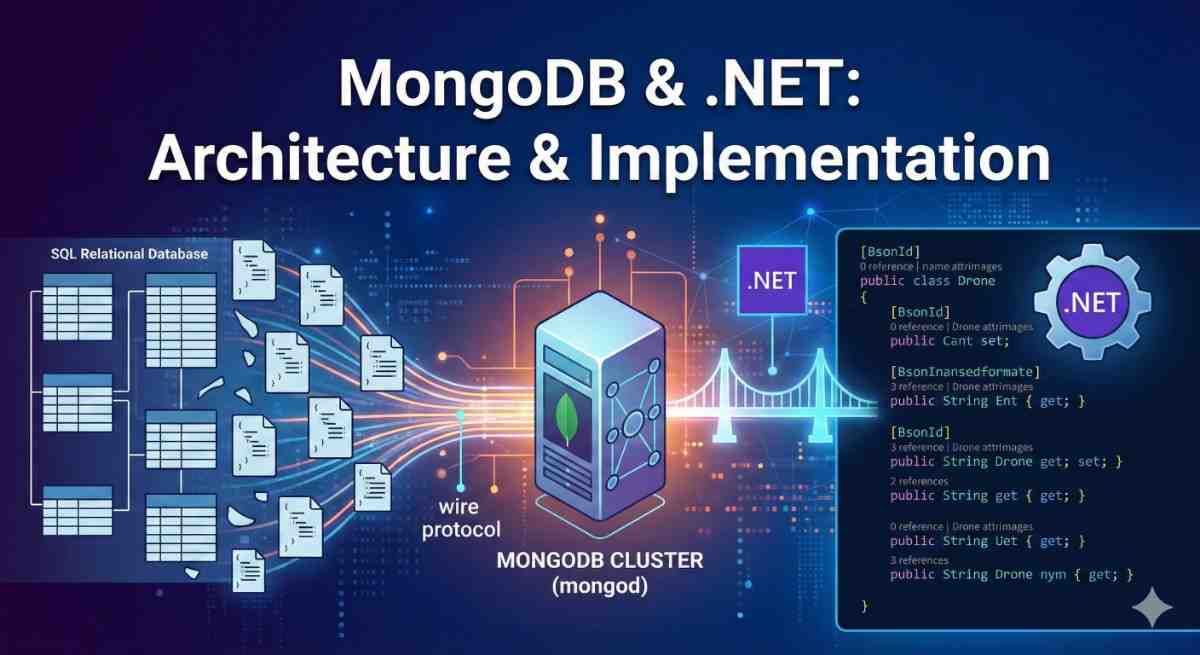

1. The Architectural Shift: JSON/BSON and the “Wire”

At its core, MongoDB abandons the tabular row-column structure for a document-oriented model. The architecture is straightforward: a client application uses a driver to communicate via a TCP/IP-based binary “wire protocol” to the mongod server process .

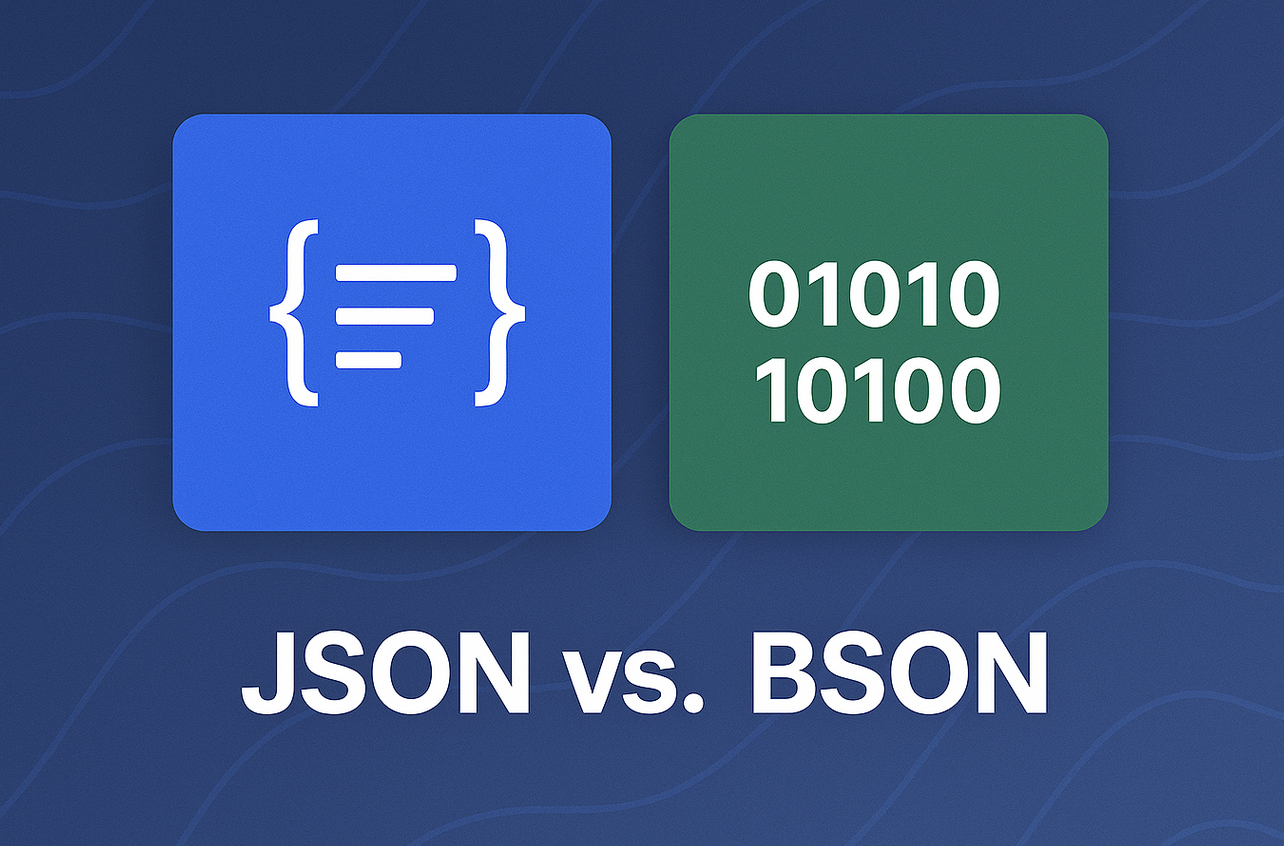

While we interact with data conceptually as JSON (JavaScript Object Notation), MongoDB stores it as BSON (Binary JSON). This is critical for engineers to understand because BSON extends JSON to include types that don’t exist in standard JSON, such as distinct integers, floats, dates, and binary data.

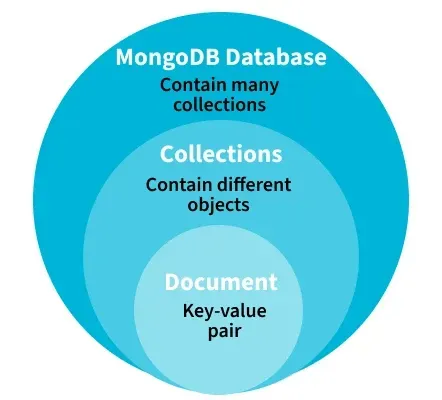

The Logical Hierarchy

Unlike the flat table structure of SQL, MongoDB organizes data hierarchically:

- Cluster: The physical deployment.

- Database: A logical container for collections (similar to a SQL Database).

- Collection: A grouping of documents (analogous to a SQL Table).

- Document: The fundamental unit of storage (analogous to a SQL Record).

Crucial Insight: Collections are schema-less. You do not define columns or data types upfront. This lack of enforced integrity allows for “polymorphic” data—similar documents with varying fields living side-by-side .

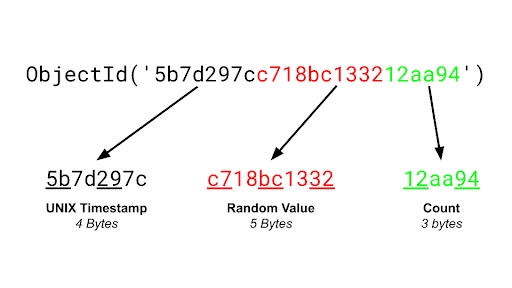

2. The ObjectId: A Lesson in Distributed Design

In the relational world, we often rely on auto-incrementing integers for Primary Keys. In a distributed NoSQL system, this causes locking contention. MongoDB solves this with the _id field, which is mandatory for every document.

If you don’t provide one, the driver generates an ObjectId. It is a 12-byte identifier designed to be globally unique without central coordination :

- Bytes 0-3: Timestamp (seconds precision).

- Bytes 4-8: Random value (derived from cluster node/process ID).

- Bytes 9-11: Counter.

This structure allows the key to inherently carry temporal information and prevents collision across distributed shards .

3. Modeling: Embedding vs. Referencing

The most common mistake developers make when moving to MongoDB is normalizing data as if it were SQL. In MongoDB, denormalization is a feature, not a bug.

Scenario: A Drone Fleet Management System

Imagine we are building a system to track autonomous drones.

Approach A: Relational Thinking (Referencing) You might create a Drones collection and a Batteries collection, linking them via ID. This is valid in MongoDB but requires application-level joins or $lookup operations.

Approach B: Document Thinking (Embedding) If a battery creates a 1-to-1 relationship with a drone and is rarely accessed independently, we embed it directly.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

{

"_id": ObjectId("507f191e810c19729de860ea"),

"model": "SkyMonitor X1",

"status": "Active",

"battery_system": {

"capacity_mah": 5000,

"cycles": 12,

"health": "Good"

}

}

Embedding is preferred for 1-to-1 relationships and improves read performance by eliminating joins .

Handling 1-to-Many

For 1-to-Many relationships, we have two paths :

- Embedding (Array): If a drone has a fixed set of rotors (e.g., 4 to 8), store them as an array within the drone document.

- Referencing: If the “Many” side is unbounded (e.g., a drone has thousands of flight logs), keep the logs in a separate collection and reference the Drone’s

_idto avoid hitting the 16MB document size limit.

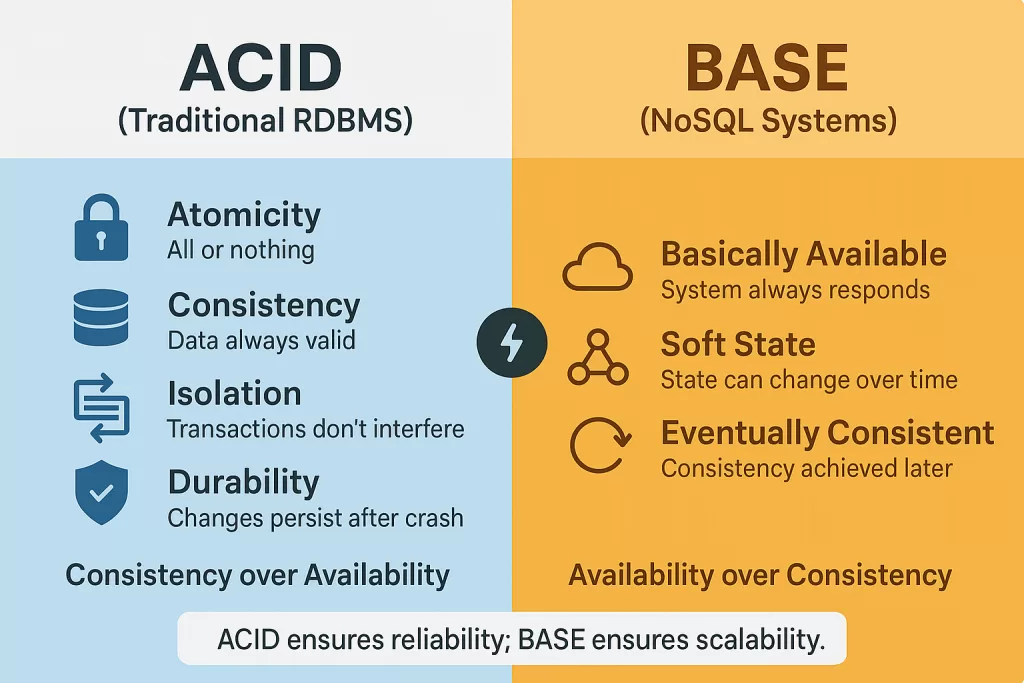

4. ACID vs. BASE

Transitioning to NoSQL requires a shift in how we view consistency.

- SQL relies on ACID (Atomicity, Consistency, Isolation, Durability).

- NoSQL typically relies on BASE (Basically Available, Soft State, Eventual Consistency).

However, MongoDB bridges this gap. Operations on a single document are always atomic. Since version 4.0, MongoDB supports multi-document ACID transactions, though they come with a significant performance penalty and should be used sparingly.

5. Implementation in .NET

The MongoDB .NET driver provides a sophisticated layer of abstraction that bridges the gap between your code and the database. It allows us to work with Plain Old CLR Objects (POCOs) rather than raw JSON or BSON documents.

Why POCOs Matter

In a raw environment, you might construct a database entry using loose strings (e.g., {"nme": "John"}). If you make a typo (“nme” instead of “name”), the compiler won’t stop you, and the database will accept the corrupt data.

The .NET driver solves this by “mapping” standard C# classes to MongoDB collections. This gives you:

- Type Safety: You cannot accidentally save a string into an integer field; the code won’t compile.

- Refactoring Support: Renaming a property in C# updates it everywhere.

- Cleaner Code: You work with objects, not dictionary-like structures.

Defining the Schema (Code-First)

We can use attributes to control how our C# classes map to BSON.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

using MongoDB.Bson;

using MongoDB.Bson.Serialization.Attributes;

public class Drone

{

// Maps this property to the MongoDB _id field

[BsonId]

public ObjectId Id { get; set; }

// Maps "ModelName" in C# to "model" in the database

[BsonElement("model")]

public string ModelName { get; set; }

// Ignores this property for persistence

[BsonIgnore]

public bool IsSelectedInUI { get; set; }

// Embedded object

public BatterySpecs Battery { get; set; }

// Array mapping

public List<string> Tags { get; set; }

}

Querying with Builders

Instead of writing raw string queries, the .NET driver offers a strongly-typed Builders class or Lambda expressions.

Example: Finding active drones with low battery

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

var collection = db.GetCollection<Drone>("drones");

// Using Lambda syntax (simple)

var results = collection.Find(d => d.Battery.Percentage < 20 && d.Status == "Active").ToList();

// Using Builders (equivalent to raw query structure)

var filter = Builders<Drone>.Filter.And(

Builders<Drone>.Filter.Lt(d => d.Battery.Percentage, 20),

Builders<Drone>.Filter.Eq(d => d.Status, "Active")

);

var resultsBuilder = collection.Find(filter).ToList();

The Aggregation Pipeline

When complex analytics are needed (like SQL GROUP BY), we use the Aggregation Pipeline. This processes documents in stages.

Example: Count drones by Model

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

var report = collection.Aggregate()

.Match(d => d.Status == "Active") // Filter first

.Group(

d => d.ModelName, // Group by Model

g => new {

Model = g.Key,

Count = g.Count()

}

)

.ToList();

If you absolutely need a “Left Outer Join,” you can use the $lookup stage, but use this cautiously as it impacts performance .

6. Advanced Updates: The Power of Operators

One of the most powerful features of MongoDB is the ability to modify specific fields without retrieving and saving the whole document.

Scenario: A drone just completed a flight. We need to update its last flight time and increment its mission counter.

1

2

3

4

5

6

var updateDef = Builders<Drone>.Update

.Set(d => d.LastFlight, DateTime.UtcNow) // Set specific field

.Inc(d => d.MissionCount, 1) // Increment counter atomically

.Push(d => d.FlightLogIds, newLogId); // Append to an array

collection.UpdateOne(d => d.Id == targetId, updateDef);

Using operators like Inc (increment), Push (add to array), and Set is far more efficient than a full document replace. We can also use Upsert (Update + Insert), which updates a document if it matches the filter, or inserts a new one if it doesn’t—crucial for processing asynchronous telemetry streams.

Final Thoughts

MongoDB is not just a “JSON store”; it is a sophisticated system that trades the strict consistency and schema of RDBMS for high availability, horizontal scaling, and flexible data modeling. By leveraging embedding over joining and utilizing atomic operators, we can build high-performance .NET applications that scale gracefully.

Attribution:This article serves as an interpretative guide based on the lecture notes “Data-driven systems: MongoDB” provided by the Department of Automation and Applied Informatics BME. Specific architectural details and driver implementations are referenced from the source material.