Refactoring and Code Smells

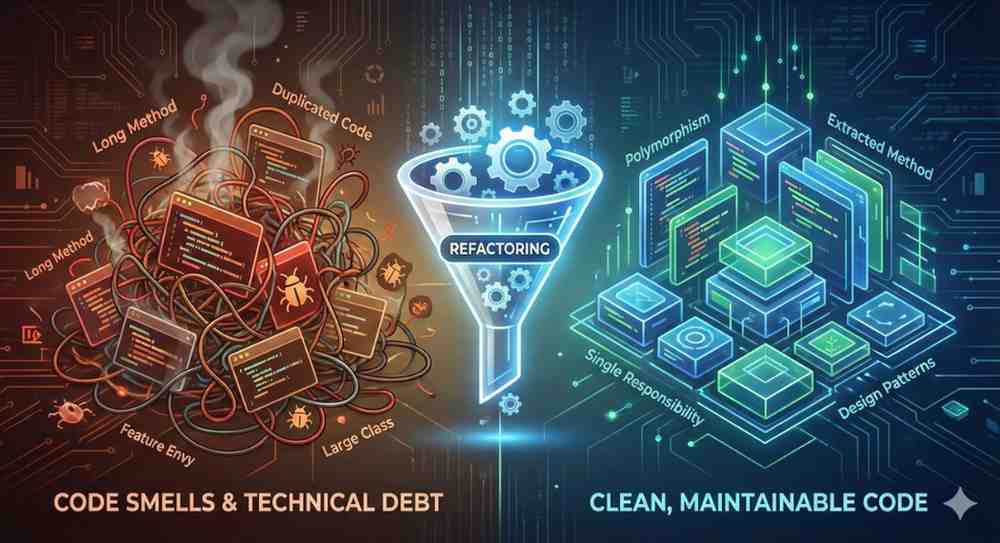

In software engineering, code is read far more often than it is written. Over time, as features are added and deadlines loom, the internal design of a software system tends to decay. This is where refactoring comes in.

According to Martin Fowler, refactoring is the process of changing the internal structure of software to make it easier to understand and cheaper to modify, without changing its observable behavior. It is not about fixing bugs or adding features; it is strictly about improving design.

But how do we know when to refactor? We look for Code Smells.

What is a Code Smell?

A “code smell” is not necessarily a bug. It is a surface indication that usually corresponds to a deeper problem in the system. They don’t prevent the program from functioning, but they indicate weaknesses in design that may increase the risk of failures or slow down development in the future.

Below is a comprehensive guide to the code smells identified in the source material, categorized by the type of design violation they represent, along with practical refactoring strategies.

1. The Bloaters

These smells represent code that has grown too large to be effectively managed.

Long Method & Large Class

The most common bloaters. A method is too long, containing too many branches, loops, or responsibilities. Similarly, a Large Class (often called a “God Class”) tries to do too much, violating the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP).

Refactoring Strategy:

- Extract Method: Break the method down. If you have a comment explaining what a block of code does, that block should probably be its own method.

- Extract Class: If a class has too many responsibilities, split it into smaller, cohesive classes.

Long Parameter List

If a method takes more than three or four parameters, it becomes difficult to read and difficult to test.

Example:

1

2

3

4

5

// Before: Hard to read and maintain

public void createInvoice(String userName, String userEmail, String userAddress, float taxRate, float discount) { ... }

// After: Refactored using "Introduce Parameter Object" [cite: 165]

public void createInvoice(UserProfile user, BillingConfig billing) { ... }

Data Clumps

This occurs when the same group of data items (e.g., x, y, z coordinates or startDate, endDate) appears together in multiple places. This is a sign that these data items belong in their own class. Refactoring strategy: Introduce Parameter Object.

2. The Object-Orientation Abusers

These smells occur when code fails to leverage true object-oriented principles (like polymorphism) and relies on procedural logic.

Switch Statements

Complex switch or if-else chains that check the type of an object are a major smell. They often lead to code duplication because adding a new type requires finding every switch statement in the codebase.

Refactoring Strategy: Use Polymorphism. Instead of asking an object “what type are you?” and then acting, simply ask the object to “do your job” and let the subclass implementation handle the specifics.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// Before: Procedural Switch

switch (employee.type) {

case ENGINEER: return salary * 1.2;

case MANAGER: return salary * 1.5;

}

// After: Polymorphism

// The logic is moved into the specific Employee subclasses

return employee.calculateBonus();

Primitive Obsession

This is the reluctance to use small objects for small tasks, such as using String for phone numbers or int for money. Primitives cannot encapsulate behavior (like validation or formatting).

Refactoring Strategy:Replace Data Value with Object. Create a PhoneNumber or Currency class.

Data Class

A class that contains only fields and getter/setter methods (dumb data holders) is a smell. It suggests that the logic which processes this data is stored elsewhere, violating encapsulation.

Refactoring Strategy:Look for where the data is being used (likely in “Feature Envy” methods) and Move Method into the Data Class so it gains real responsibility.

Refused Bequest

This occurs when a subclass inherits methods or data from a parent class but only uses a fraction of them. It suggests the hierarchy is wrong (the “Child” isn’t truly a version of the “Parent”). A common symptom is a subclass overriding a method just to make it throw a NotImplementedException.

Refactoring Strategy:

- If the inheritance makes sense but the parent has too much specific logic: Push Down Method or Push Down Field to move the unused parts to a sibling class.

- If the subclass and parent are entirely different concepts (e.g., a

Stackinheriting fromListjust to reuse code): Replace Inheritance with Delegation. Remove the inheritance link and give the subclass a field that holds the “Parent” object instead.

3. The Couplers

These smells represent high coupling between classes, making the system fragile.

Feature Envy

This occurs when a method in one class is more interested in the data of another class than its own.

Example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

// Class: ReportGenerator

// Smell: The method uses mostly 'user' data, not ReportGenerator data.

public String getUserSummary(User user) {

return user.getName() + " lives at " + user.getAddress() + " (" + user.getZip() + ")";

}

// Refactoring: Move Method [cite: 217]

// Move this logic into the User class itself.

Message Chains

This is often seen as getA().getB().getC().doSomething(). The client is coupled to the navigation structure of the class graph. If A changes how it references B, the client breaks. This violates the Law of Demeter.

Refactoring Strategy: Hide Delegate. Create a method on A that delegates to C, preventing the client from seeing the chain.

Inappropriate Intimacy

Classes that know too much about each other’s private parts. This creates tight coupling. Refactor by moving methods or fields to reduce this dependency.

4. The Change Preventers

These smells make code rigid; simple changes become expensive.

Divergent Change vs. Shotgun Surgery

These two are often confused but are opposites:

- Divergent Change: You make many different types of changes to one single class (e.g., modifying the same class for DB changes, UI changes, and business logic).

- Fix: Extract Class. Separate the distinct responsibilities.

- Shotgun Surgery: You make one logical change (e.g., adding a currency type), but you have to make small edits to many different classes. The sub-problem of this code smell is

Excessive use of literals.- Fix: Move Method/Field. Consolidate the dispersed logic into a single class.

- Replace magic numbers with symbolic constant

- Fix: Move Method/Field. Consolidate the dispersed logic into a single class.

5. The Dispensables

Code that provides no value and should be removed.

- Duplicated Code: The most critical smell. It violates the DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself) principle. Always Extract Method or Extract Class to unify logic.

- Lazy Class: A class that doesn’t do enough to justify its existence. Fix by Collapsing Hierarchy or Inline Class.

- Speculative Generality: “We might need this someday.” This leads to over-engineered machinery for features that don’t exist yet. Delete the unused code (YAGNI - You Ain’t Gonna Need It).

- Comments: While comments are good, using them to explain bad code is a smell. If you feel the need to write a long comment explaining what a block does, you should instead Extract Method and name the method what the comment said.

How to Refactor Safely: The Golden Rules

Refactoring is powerful, but it carries risk. The source material outlines critical rules to ensure safety:

- Three Strikes Rule: Do not refactor prematurely.

- 1st time: Just do it.

- 2nd time: You wince at duplication, but do it anyway.

- 3rd time: Refactor.

- Solid Tests are Mandatory: You cannot refactor safely without a comprehensive suite of unit tests. Since refactoring changes structure, you need tests to prove you haven’t broken functionality.

- Take Small Steps: Make a small change, run tests, repeat. If a test fails, it is easy to undo and find the bug.

Matching Refactoring Patterns with Code Smells

| Code Smell | Refactoring Method |

|---|---|

| Long Method | Extract Method |

| Large Class | Extract Class, Extract Subclass |

| Duplicated Code | Extract Method, Pull Up Method |

| Feature Envy | Move Method, Extract Method |

| Primitive Obsession | Replace Data Value with Object, Replace Type Code with Class |

| Switch Statements | Replace Conditional with Polymorphism |

| Data Clumps | Extract Class, Introduce Parameter Object |

| Message Chains | Hide Delegate |

| Inappropriate Intimacy | Move Method, Move Field |

| Lazy Class | Inline Class, Collapse Hierarchy |

| Data Class | Move Method to Data Class |

| Speculative Generality | Delete the unused code |

| Comment Explanations | Extract Method |

| Shotgun Surgery | Move Method/Field (consolidate the dispersed logic in single class) |

| Divergent Change | Extract Class |

| Long Parameter List | Preserve whole object |

| Refused Bequest | Push Down Method / Push Down Field OR Replace inheritance with delegation* |

Replace Inheritance with Delegation only if subclass and parent are entirely different concepts.

Summary

Refactoring improves design, helps find bugs, and actually speeds up programming in the long run. By identifying these smells—from the “Bloaters” like Long Method to the “Couplers” like Feature Envy—you can actively pay down technical debt and keep your software healthy.

Source Acknowledgment:This post is based on my personal notes and interpretation of the “Object-Oriented Design - Refactoring” lecture materials by Dr. Balázs Simon (BME, IIT).