Static Analysis (SAST) & Building Your Own Rules

As penetration testers and software engineers, we often obsess over dynamic attacks—SQL injection payloads, XSS vectors, and runtime exploits. But what if you could catch the vulnerability before the code is even compiled?

Enter Static Analysis (often called SAST in the security world). It’s not just a “spellchecker” for your code; it is an automated way to reason about the runtime properties of your software without ever hitting the “Run” button.

In this post, we’ll dive into how static analysis works, why it’s critical for preventing security debt, and—crucially—how to spin up your own analysis server and write custom rules to catch project-specific issues.

What is it, really?

Think of Dynamic Analysis (DAST) as a crash test: you drive the car into a wall to see if the airbag deploys. Static Analysis, on the other hand, is like a blueprint review: an engineer looks at the schematics and says, “Hey, you forgot to draw the line connecting the airbag sensor to the inflator.”

The goal is to find problems that are computationally complex or “undecidable” to find during manual testing. These tools scan your source code to detect:

- Security Vulnerabilities: Weak cryptography, hardcoded credentials, injection flaws.

- Reliability Issues: Resource leaks, null pointer dereferences.

- Bad Practices: Violating coding standards (like MISRA or Google Style Guides).

The “False Positive” Dilemma

If you’ve ever run a security scan, you know the pain of sifting through 500 warnings where 490 are useless. This happens because static analysis relies on approximations. To save time, the analyzer sacrifices some precision. This leads to two outcomes you need to understand:

- False Positive: The tool flags code as vulnerable, but it’s actually safe. This causes “alert fatigue.”

- False Negative: The tool says the code is clean, but a bug exists. This is dangerous in security contexts.

Pro Tip: Don’t aim for zero warnings immediately. Configure your tools to filter by “Severity” or specific vulnerability categories (like OWASP Top 10) first.

Code in Action: What the Scanner Sees

Let’s look at two common patterns that tools like SonarQube, SpotBugs, or Coverity excel at finding.

1. The Resource Leak (Availability / DoS Risk)

A common issue in Java/C++ is failing to close resources (files, sockets, database connections). In a security context, an attacker could trigger this path repeatedly to exhaust server resources, causing a Denial of Service (DoS).

The Vulnerable Pattern:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

public void readConfidentialData(String path) {

try {

// SCANNERS catch this: "Resource not closed on all paths"

FileInputStream fis = new FileInputStream(path);

Scanner scanner = new Scanner(fis);

// Imagine an exception happens here while parsing

String secret = scanner.nextLine();

scanner.close(); // If line above fails, this never runs!

} catch (IOException e) {

System.out.println("Failed to read secrets.");

}

}

The Static Analysis Fix: The tool identifies that the .close() method is not reachable in the catch block. It forces you to use a finally block or “try-with-resources.”

2. The Null Pointer Dereference (Reliability / Crash)

While often seen as just a “bug,” a Null Pointer Exception (NPE) is a reliability flaw. If an unauthenticated user can crash your API by sending a missing field, you have an Availability vulnerability.

The Vulnerable Pattern:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

public void processUser(User user) {

// Static Analysis Flag: "user" might be null here

String username = user.getName();

if (user != null) {

System.out.println("Logged in: " + username);

}

}

What the Tool Sees: The analyzer constructs a Control Flow Graph (CFG). It notices you checked if (user != null) after you already accessed user.getName(). This logical inconsistency is a classic pattern tools like Infer or SpotBugs catch immediately.

Hands-On: Building Your Own Analysis Lab

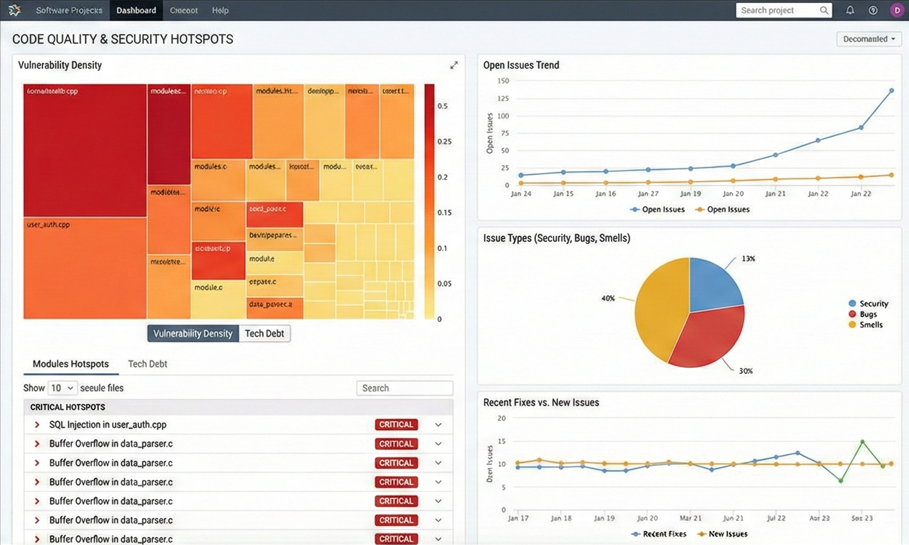

Understanding the theory is great, but to really master SAST, you need to run the infrastructure. While VS Code extensions (like SonarLint) are great for personal feedback, you need a Server to track project health over time and enforce rules for a team.

Here is the fastest way to get a professional-grade setup running locally using Docker.

1. The Server Setup

Instead of installing messy dependencies, we use the official Docker image with docker-compose.yml file where all settings and volumes are given.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

services:

sonarqube:

image: sonarqube:community

read_only: true

volumes:

- sonarqube_data:/opt/sonarqube/data

- sonarqube_extensions:/opt/sonarqube/extensions

- sonarqube_logs:/opt/sonarqube/logs

- sonarqube_temp:/opt/sonarqube/temp

ports:

- "9000:9000"

networks:

- ${NETWORK_TYPE:-ipv4}

volumes:

sonarqube_data:

sonarqube_extensions:

sonarqube_logs:

sonarqube_temp:

networks:

ipv4:

driver: bridge

enable_ipv6: false

dual:

driver: bridge

enable_ipv6: true

ipam:

config:

- subnet: "192.168.1.0/24"

gateway: "192.168.1.1"

- subnet: "2001:db8:1::/64"

gateway: "2001:db8:1::1"

Run this one-liner in your terminal:

1

2

sudo docker-compose up -d #bash

docker compose up -d #powershell

Once it starts (give it a minute!), open http://localhost:9000 (Default login: admin / admin). You now have a centralized dashboard to track “Technical Debt” and “Security Hotspots.”

2. Extending the Brain: Custom Plugins

This is where you move from “tool user” to “security engineer.” Sometimes, the built-in rules aren’t enough. Maybe your company has a specific crypto library you must use, or you want to ban System.out.println because it leaks sensitive logs to the console.

To add a new rule, you don’t just write a script; you build a Plugin. A standard SonarQube rule requires three specific components (the “Three Pillars”) to work:

- The Logic (Java): The code that visits the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) to find the bug.

- The Metadata (JSON): The configuration that tells the server if this is a “Bug” or a “Vulnerability,” and how severe it is.

- The Registration (Java): The wiring that tells the plugin, “Hey, I have a new rule for you to load.”

Step 1: The Logic (The Brain)

We extend a IssuableSubscriptionVisitor. This allows us to “subscribe” to specific parts of the code syntax, like method calls or variable declarations.

Example: Banning System.out.println We want to catch any call to println on the System.out object.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

@Rule(key = "NoSystemOut") // Matches the JSON key later

public class NoSystemOutCheck extends IssuableSubscriptionVisitor {

@Override

public List<Tree.Kind> nodesToVisit() {

// Efficiency: Only wake up for Method Calls

return Collections.singletonList(Tree.Kind.METHOD_INVOCATION);

}

@Override

public void visitNode(Tree tree) {

MethodInvocationTree methodCall = (MethodInvocationTree) tree;

// Check: Is it a call to "println"?

if (methodCall.methodSelect().lastToken().text().equals("println")) {

// Report the error right on the code line

reportIssue(tree, "Security Risk: Use a proper Logger (like Slf4j), not System.out");

}

}

}

Step 2: The Metadata (The Face)

The Java class finds the issue, but the Server needs to know how to display it. You create a JSON file (e.g., NoSystemOut.json) in your resources folder.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

{

"title": "Avoid using System.out.println",

"type": "VULNERABILITY",

"status": "ready",

"severity": "MAJOR",

"tags": [

"cwe-532",

"security"

]

}

- Type: Is it a

BUG,VULNERABILITY, orCODE_SMELL? - Severity:

BLOCKERwill fail the build immediately;INFOis just a note. - Tags: specific tags like

cwe-532(Information Exposure via Log Files) help audit teams track compliance.

Step 3: The Registration (The Wiring)

Finally, you must register your rule in the Plugin’s “Rules List.” If you skip this, your code compiles, but the server will never run it.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

public final class RulesList {

public static List<Class<? extends JavaCheck>> getJavaChecks() {

return Arrays.asList(

NoSystemOutCheck.class,

AnotherCustomRule.class

);

}

}

Step 4: Verification (The Test)

Before deploying, you shouldn’t just hope it works. Sonar provides a CheckVerifier tool that lets you unit test your rule against a snippet of Java code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

@Test

void verifyRule() {

// Fails the test if the rule doesn't flag the error on line 5

CheckVerifier.newVerifier()

.onFile("src/test/files/VulnerableCode.java")

.withCheck(new NoSystemOutCheck())

.verifyIssues();

}

3. Deploying Your Rule

Once you compile your plugin with Maven (mvn package), you get a single .jar file. Deploying it is as simple as copying it into the Docker container:

1

2

docker cp target/my-security-rules.jar sonarqube:/opt/sonarqube/extensions/plugins/

docker restart sonarqube

After the restart, go to Quality Profiles, create a custom profile (e.g., “SecOps Way”), and activate your new rule. Now, any project scanned by your server will fail if it violates your custom security policy!

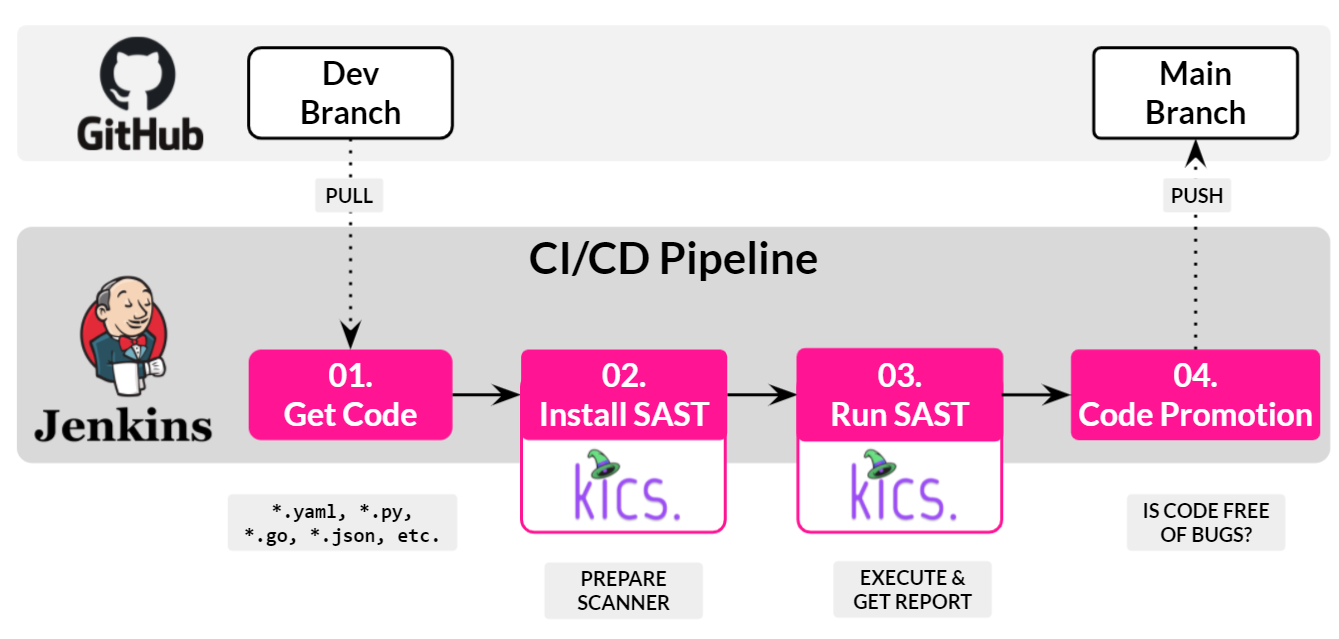

Order in CI/CD

Question: Can I run advanced static analysis on just the .java source files? Answer: Technically yes, but the results will be poor.

Deep analysis (finding complex bugs) requires Type Resolution. The scanner needs to know that user.getName() returns a String and not an Integer. To do this effectively, tools like SonarQube often require access to the compiled binaries (the .class files) and the dependencies (libraries).

This is why your CI/CD pipeline usually runs mvn build before mvn sonar:sonar. If the scanner can’t read the compiled bytecode, it effectively becomes a “dumb” text search.

Integrating into the Workflow (DevSecOps)

The biggest mistake teams make is running these scans only before a release. By then, the “Technical Debt” is too high to fix.

To make this useful for cybersecurity:

- Shift Left: Integrate the scanner into your CI/CD pipeline (Jenkins, GitHub Actions).

- Quality Gates: Set a hard fail condition. “If Security Rating is worse than A, fail the build.”

- Code Review: Use the scanner’s report during Pull Requests. It acts as an automated reviewer that never gets tired.

Integrating Static Analysis checks (SAST) into the commit phase prevents vulnerabilities from reaching production.

Conclusion

Static analysis isn’t a silver bullet—it won’t find every logical flaw or architectural vulnerability. However, it is the most cost-effective way to eliminate entire classes of bugs (like resource leaks and null pointers) before they ever become security incidents.

For us in the security field, it’s about reducing the attack surface. Every bug fixed by a static analyzer is one less foothold for an attacker.