The Art of Static Verification: shifting Quality Left

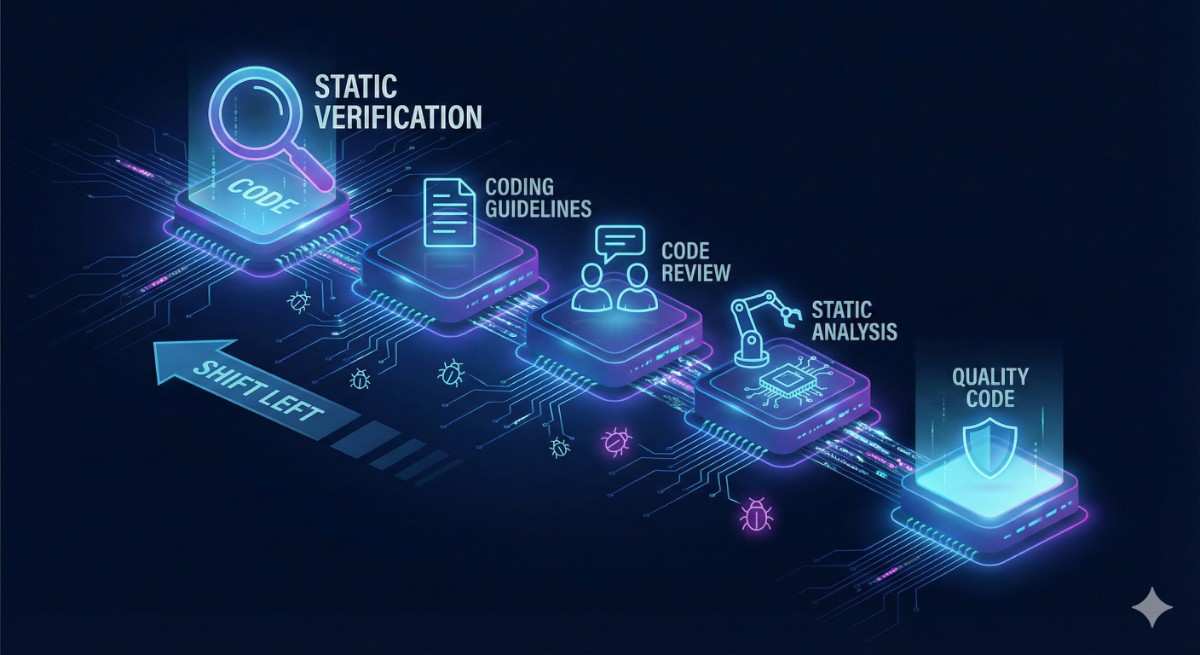

In the modern software development lifecycle (SDLC), the cost of fixing a bug grows exponentially the later it is discovered. A defect found in production might cost 100x more to fix than one found during the design or coding phase. This reality has driven the industry toward a "Shift Left" mentality—moving verification and validation as early in the process as possible.

Based on recent research into automated software engineering, this post synthesizes the three pillars of static verification: Coding Guidelines, Code Reviews, and Static Analysis. We will explore how these mechanisms work together to ensure code quality without ever running the executable.

1. The First Line of Defense: Coding Guidelines

Before we even discuss finding bugs, we must agree on what “good code” looks like. Coding guidelines are not just about aesthetics; they are about minimizing cognitive load and avoiding constructs known to be dangerous.

The Hierarchy of Rules

Guidelines generally fall into three categories, ranging from broad industry standards to specific organizational quirks:

- Industry-Specific: In safety-critical sectors like automotive or aerospace, guidelines are rigorous. For example, MISRA C is a standard used in the motor industry that restricts the C language to a safer subset. It enforces strict rules, such as ensuring loop bodies are always enclosed in braces or forbidding certain side effects in boolean operations, to prevent ambiguity and undefined behavior.

- Platform-Specific: These rules ensure your code plays nicely with the ecosystem. For instance, the .NET Framework Design Guidelines focus on API usability, advising developers on when to make classes abstract or how to name constructor parameters to match properties.

- Organization-Specific: Companies like Google or CERN maintain their own style guides to ensure consistency across massive codebases. These often dictate file structures, naming conventions (e.g., prohibiting Hungarian notation or specific prefixes), and error handling practices.

For more detailed information on Clean Code practices read: The Art of Clean Code https://4ykh4ncyb3r.github.io/posts/clean_code/

Enforcement

A style guide exists only in theory until it is enforced. Relying on memory is insufficient. Effective engineering teams embed these rules into their Integrated Development Environments (IDEs) or use external formatters to ensure compliance automatically.

2. The Human Filter: Code Review

While automated guidelines handle style, Code Reviews handle intent and logic. This is a manual process where humans examine source code to identify errors, ensuring the software is readable, maintainable, and secure.

The Spectrum of Formality

Code reviews can range from casual “over-the-shoulder” checks to rigorous inspections:

- Informal Reviews: Often ad-hoc, performed by a peer or lead, and focused on quick feedback.

- Formal Inspections: A documented process involving moderators and specific entry/exit criteria. This is historically more effective at error finding but is time-consuming.

The Modern Workflow

Today, most teams utilize a “Pull Request” (PR) model integrated into platforms like GitHub. This workflow facilitates asynchronous discussion, allowing reviewers to block merges until specific concerns—commented directly on the relevant lines of code—are resolved.

Beyond catching bugs, code reviews are a critical vector for knowledge transfer. They help junior engineers learn the codebase, foster team spirit, and expose the team to alternative problem-solving approaches.

3. The Automated Enforcer: Static Analysis

Static analysis is the automated reasoning about the runtime properties of code without executing it. While testing verifies that the code works for specific inputs, static analysis attempts to prove the code is robust across all possible execution paths.

The Precision Paradox

Ideally, we want an analysis that finds every bug (soundness) without ever complaining about correct code (completeness). In reality, determining non-trivial runtime properties is computationally undecidable. Therefore, static analysis tools must approximate, leading to a trade-off:

- False Positives (False Alarms): The tool reports an error where none exists. If a tool cries wolf too often, developers will stop listening.

- False Negatives (Missed Bugs): The tool remains silent despite the presence of a critical flaw. This gives a false sense of security.

Techniques and Categories

Static analysis tools generally fall into two methodologies:

- Pattern-Based (Linting): These tools look for syntax patterns that suggest bugs, such as unused variables, ignored return values, or “dead” stores. Tools like

ErrorProneorFindBugs/SpotBugsexcel here, catching issues like “loop conditions that are never modified” or “hashCode() generated but equals() not overridden”. - Interpretation-Based (Deep Analysis): These tools attempt to simulate execution paths abstractly to find complex issues like null pointer dereferences, resource leaks, or index-out-of-bounds errors. Examples include verification platforms like

CoverityorInfer.

A Conceptual Example: Resource Leaks

Consider a scenario where a database connection is opened inside a try block. If an exception occurs before the connection is closed, and the close call is not in a finally block, the resource leaks. A simple compiler won’t catch this, and unit tests might pass if the exception path isn’t triggered. A static analyzer, however, traces the path and flags the missing cleanup obligation.

4. The Tooling Ecosystem

The market is saturated with powerful tools designed to catch these issues:

SonarQube: A comprehensive quality management platform that tracks “technical debt,” code smells, and vulnerabilities over time, visualizing trends in dashboards.

- SonarLint: An IDE plugin that acts as a spell-checker for code, providing instant feedback as you type.

- Coverity: A heavyweight commercial tool used by organizations like CERN and NASA, known for deep analysis of C/C++ and Java.

5. Strategic Implementation

Integrating static analysis into a project isn’t as simple as installing a plugin. If you enable every rule on a legacy codebase, you will likely be overwhelmed by thousands of warnings.

Best Practices for Adoption:

- Integrate into CI/CD: Make checks part of the build process. Fail the build if new critical bugs are introduced.

- Filter and Tune: Start with a high-severity filter. Don’t let minor style warnings obscure critical security flaws.

- Baseline the Legacy: When introducing a tool, focus on new code (the “leak period”). Don’t try to fix five years of technical debt in one day.

- Handle False Positives: When a tool is wrong, suppress the warning but always document why it is safe in the code comments.

Conclusion

Static verification is not a replacement for testing, but a complement. By leveraging coding guidelines, human review, and automated static analysis, we can catch subtle errors—concurrency deadlocks, resource leaks, and security vulnerabilities—before the code ever leaves the developer’s machine.

Attribution:This blog post is a synthesis of concepts and insights derived from “Static Analysis” provided by the Department of Measurement and Information Systems at BME.