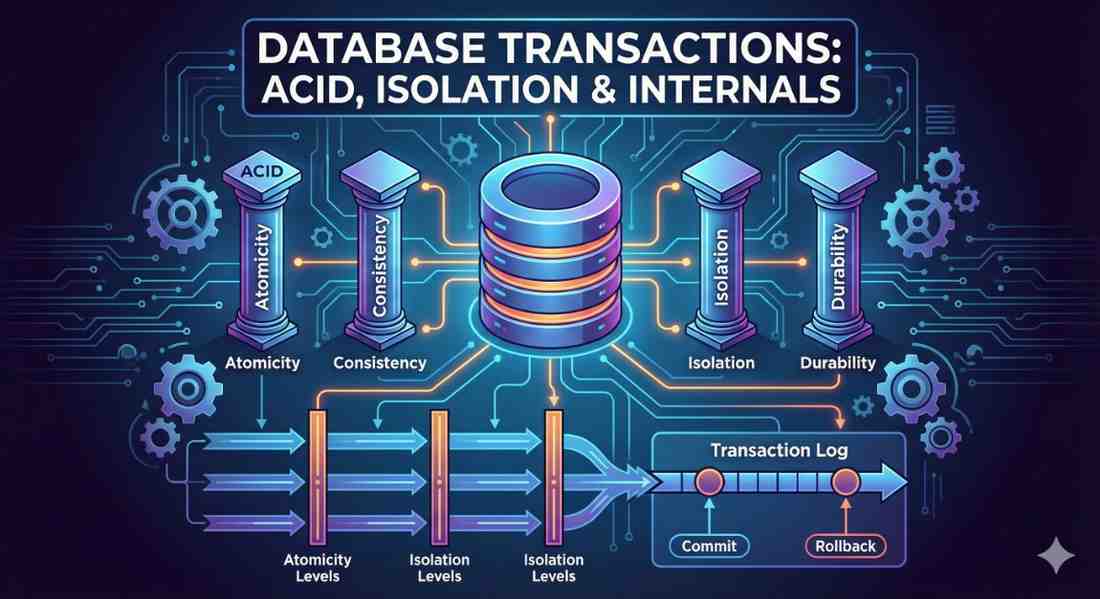

Database Transactions: ACID, Isolation, and Internals

In modern software architecture, managing state is the hardest problem we face. Whether you are building a high-frequency trading platform or a simple e-commerce backend, the integrity of your data relies heavily on how your database handles concurrent operations and system failures.

Today, I’m digging into the mechanics of Transactions. We’ll move beyond the basic BEGIN and COMMIT keywords to understand the underlying theory of ACID properties, the notorious race conditions that occur in concurrent environments, and the low-level logging mechanisms databases use to guarantee durability.

What is a Transaction?

Fundamentally, a transaction is a logical unit of processing. It is a sequence of operations that, from the application’s perspective, effectively “only make sense together”.

Imagine an e-commerce scenario where a user purchases a limited-edition sneaker. The system must do two things:

- Decrement the inventory count for that sneaker.

- Create a purchase record for the user.

If the inventory is decremented but the server crashes before the purchase record is created, we have a “phantom” inventory loss. If the record is created but the inventory isn’t decremented, we sell stock we don’t have. A transaction wraps these operations into a single boundary.

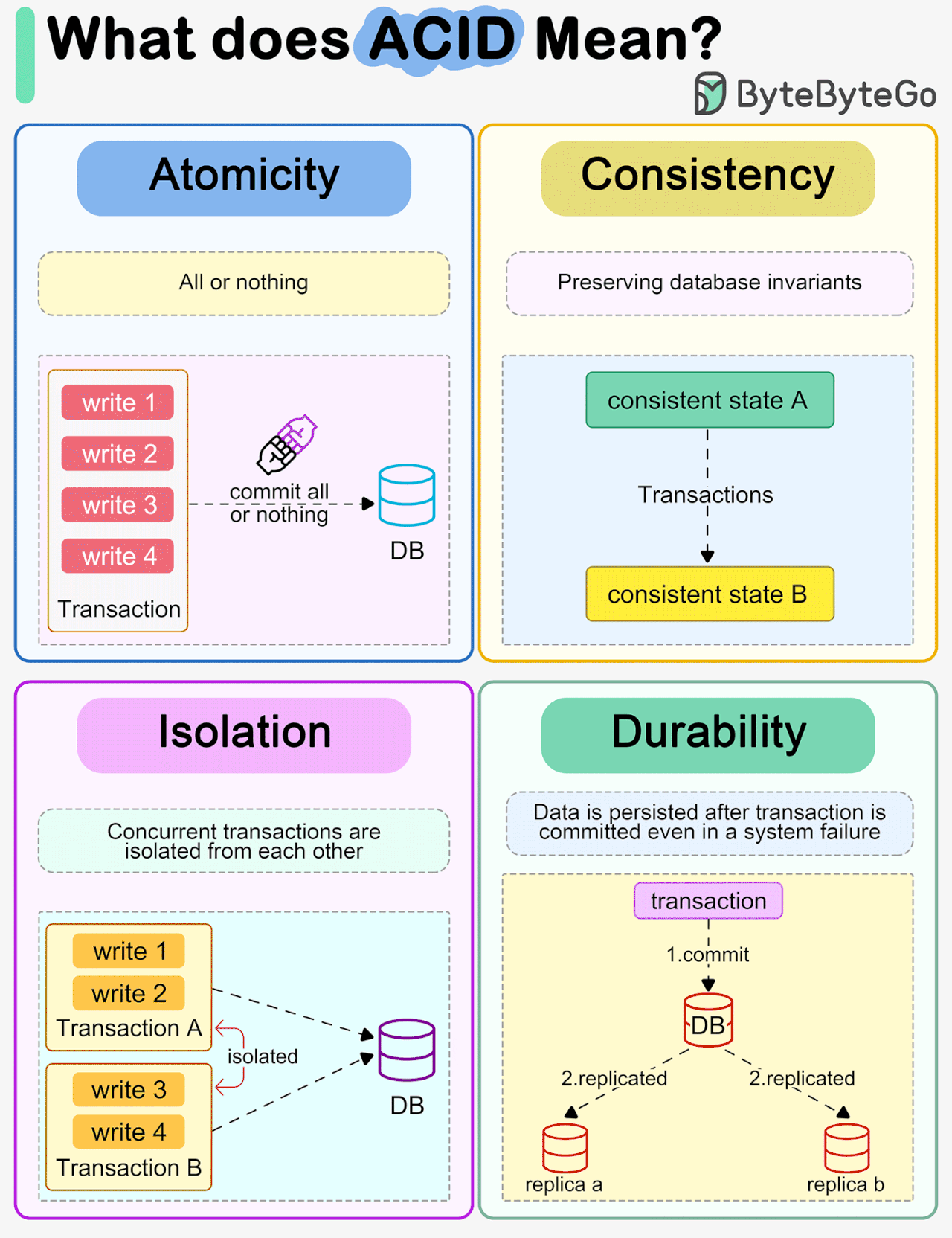

The ACID Standard

To ensure reliability, transactional systems adhere to four properties known as ACID.

1. Atomicity

Atomicity guarantees that the transaction is treated as a single “all-or-nothing” unit. If any statement inside the transaction fails, the entire transaction is aborted, and the database state is rolled back to where it was before the transaction began.

Example: In our sneaker shop, if the payment gateway times out after we’ve locked the stock, the database must automatically revert the stock lock.

2. Consistency

Consistency ensures that a transaction brings the database from one valid state to another valid state. The data must adhere to all defined rules, constraints, and cascades (e.g., referential integrity or positive integer constraints on inventory).

3. Isolation

Isolation is the property that deals with concurrency. It ensures that the intermediate state of a transaction is invisible to other transactions. Essentially, multiple transactions executing concurrently should produce the same result as if they were executed serially (one after the other).

4. Durability

Durability guarantees that once a transaction has been committed, it will remain committed even in the event of a system failure (e.g., power loss or crash). This is typically achieved via transactional logging, which we will discuss later.

Concurrency and Isolation Problems

When we scale systems, we rarely have the luxury of running transactions one at a time. We run them concurrently to handle load. However, without proper isolation, concurrent access to shared data leads to specific “phenomena” or race conditions.

Here are the four classic isolation failures you must know:

1. Dirty Read

A dirty read occurs when Transaction A reads data that Transaction B has modified but not yet committed. If B rolls back later, A is holding data that technically never existed.

Scenario:

- Transaction A: Updates Item #50 price to $100 (uncommitted).

- Transaction B: Reads Item #50 price as $100.

- Transaction A: Rolls back (Price reverts to $50).

- Result: Transaction B processes a sale at $100, which is wrong.

2. Lost Update

This happens when two transactions read the same value and update it, but one overwrites the other’s work blindly.

Code Scenario:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

-- Initial Stock: 10

-- Transaction A

SELECT Stock FROM Inventory WHERE ID = 1; -- Reads 10

-- Transaction B

SELECT Stock FROM Inventory WHERE ID = 1; -- Reads 10

-- Transaction A

UPDATE Inventory SET Stock = 11 WHERE ID = 1; -- A sets to 11 (10+1)

COMMIT;

-- Transaction B

UPDATE Inventory SET Stock = 11 WHERE ID = 1; -- B sets to 11 (10+1)

COMMIT;

-- Final Result: 11 (Should be 12)

3. Non-Repeatable Read

This occurs when a transaction reads the same row twice but gets different data because another transaction modified committed data in between the reads.

Scenario:

- Transaction A:

SELECT Status FROM Orders WHERE ID=100-> Returns “Pending”. - Transaction B:

UPDATE Orders SET Status='Shipped' WHERE ID=100; COMMIT; - Transaction A:

SELECT Status FROM Orders WHERE ID=100-> Returns “Shipped”. - Result: Logic within Transaction A that depended on the status remaining constant is now broken.

4. Phantom Read

A phantom read happens when a transaction runs a query returning a set of rows that satisfy a search condition, but a second transaction inserts or deletes rows that match that condition. When the first transaction re-runs the query, it sees a different set of “phantom” rows.

Scenario:

- Transaction A:

SELECT * FROM Orders WHERE Date = 'Today'(Returns 5 rows). - Transaction B: Inserts a new order for ‘Today’ and Commits.

- Transaction A:

SELECT * FROM Orders WHERE Date = 'Today'(Now returns 6 rows). - Result: Aggregations or reports generated by A will be inconsistent.

Solutions: Isolation Levels

The SQL standard defines four isolation levels to handle these problems. Higher isolation provides better consistency but often reduces performance due to locking overhead.

| Isolation Level | Dirty Read | Non-Repeatable Read | Phantom Read |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Uncommitted | Allowed | Allowed | Allowed |

| Read Committed | Prevented | Allowed | Allowed |

| Repeatable Read | Prevented | Prevented | Allowed |

| Serializable | Prevented | Prevented | Prevented |

Implementation Strategies

Pessimistic Locking (Traditional)

This approach uses locks to block access. If Transaction A writes to a record, it places a lock (exclusive) on it. Transaction B cannot read or write to that record until A finishes.

- Pros: Prevents conflicts absolutely.

- Cons: High risk of deadlocks; reduces concurrency significantly.

Optimistic / Snapshot Isolation (Modern)

Instead of locking reading resources, the database uses Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC). When a transaction starts, the database provides a “snapshot” of the data as it existed at that moment.

- Writers copy the record to a temporary area (like

tempdb) before modifying it (Copy-on-Write). - Readers continue to read the old version from the snapshot.

- Conflict Resolution: If two transactions try to modify the same data, the collision is detected at commit time, and one transaction is killed.

- Use Case: Ideal for systems with heavy reads and fewer writes.

Deep Dive: Durability and Logging

How does a database ensure Durability? If the power plug is pulled 10ms after a commit, how is the data saved? The answer lies in the Transaction Log (often called the Write-Ahead Log).

Disk I/O is expensive. Writing to the actual database files (random access) is slow. Writing to a log (sequential append) is fast. Therefore, databases prioritize the log.

There are three main logging strategies:

1. Undo Logging

In this strategy, the database records the old value (pre-modification) in the log.

- Process:

- Read data to memory.

- Log the old value (e.g.,

Value=10). - Modify the data in memory/DB.

- To Commit: The database file MUST be written to disk before the commit log entry is made.

- Recovery: If a crash happens, the system reads the log backwards and “Undoes” any transaction that doesn’t have a commit marker.

2. Redo Logging

Here, the database records the new value (post-modification) in the log.

- Process:

- Read data to memory.

- Log the new value (e.g.,

Value=11). - To Commit: The log entry MUST be written to disk before the database file is touched.

- Recovery: The system reads the log from the beginning and “Redoes” (re-applies) the changes for committed transactions.

3. Undo/Redo Logging (Hybrid)

This is the most robust method. It logs both the old and new values.

- Advantage: The commit entry can be written to the log regardless of whether the database file has been updated yet. This decouples the “Log Write” from the “Data Write,” allowing for better internal synchronization and performance.

- Recovery: During recovery, the system Redoes committed transactions and Undoes interrupted ones.

Note: Transaction logs must be truncated periodically (checkpoints), or they will grow indefinitely, especially with long-running transactions.

Distributed Transactions

Scaling beyond a single server introduces the CAP Theorem, which states a distributed data store can only provide two of the following three: Consistency, Availability, and Partition Tolerance.

In a distributed environment (e.g., microservices using AWS/Azure), maintaining ACID properties requires complex coordination, often managed by a Two-Phase Commit (2PC) protocol. However, this creates a tightly coupled system.

Eventual Consistency

To maintain high availability (Amazon, Facebook), many modern systems sacrifice Strong Consistency for Eventual Consistency.

- Strong Consistency: All nodes see the same data at the same time.

- Eventual Consistency: Reads might return stale data for a short “inconsistency window,” but all nodes will eventually sync up.

For long-running distributed processes (like a travel booking that spans flights, hotels, and car rentals), we often use the Saga Pattern. Instead of a single database lock, Sagas break the transaction into smaller local transactions. If one fails, the system executes “compensating transactions” (e.g., issuing a refund) to restore consistency manually.

Summary:

Understanding transactions separates a coder from an engineer. It’s about knowing that isolation level isn’t just a config setting—it’s a choice between data accuracy and system throughput. It’s about understanding that your data is only as safe as your logging strategy.

Acknowledgment: Based on my interpretation of the “Data-driven systems: Transactions” educational materials by BME JUT / SME INT.